The first thing you see at Jafbox, Joseph Fraioli’s studio in West Los Angeles, is a modular synth. Just looming there, looking like an obsessive detective’s crazy wall. Jumbles of colored patch cords traverse it wildly, connecting modules together in ways that make sense only to him.

Synthesizers are made up of individual parts: oscillators produce tones, filters affect their timing, other filters affect the dynamics or feel of the tones. Most synths only let you blend the individual parts in the specific order that the designer has hard wired them. But modular synths break you out of that, letting you blend parts as you wish, ad infinitum. Exploring their possibilities is a life-long journey best suited to obsessives, alchemists, and meanderers.

Obsessive meandering alchemy is an apt description of Fraioli’s career as a sound designer and electronic musician. Fraioli, who relocated from New York in 2018, has been releasing electronic music as Datach’i since the late 90s on labels like Planet Mu and Timesig (owned by Aaron Funk/Venetian Snares). Throughout the years, he’s played with the limits of genres like drum-n-bass and techno. Sometimes his work explores the playful and melodic, other times the intense and dissonant. Fraioli’s consistency is rooted in being open, experimental, and flexible — qualities that have served him well in the world of sound design.

Fraioli’s resume in sound design is multi-layered, informed by years of investigating the possibilities of individual parts. He’s built complex, immersive installations for Kanye West at Cannes and, as a solo artist, at the Walker Art Center. He’s also created dozens of rich, sonic worlds on commercials, television series, and films (most recently on Kin, starring Dennis Quaid, Zoe Kravitz, and James Franco). In this interview with writer and musician Kerry McLaughlin, he discusses how his varied background has given him a unique approach to sound design and how staying open to accidents is the key to success. (more…)

Ask any documentary director worth their salt where films really get made and they’ll confess: the edit. It’s the editor who combs through hours and hours of footage hunting for the threads that’ll weave the tapestry of the story together.

In this respect, Lindsay Utz is at the top of her game. Her latest project, American Factory, follows a Chinese billionaire who opens a car-glass factory in an abandoned General Motors plant in Ohio. Early optimism gives way to setbacks as high-tech China clashes with working-class America. The film combines humor with heartbreak, the duality that drew Utz to the story.

She’s eschewed the current trend toward slick, over-produced documentaries in exchange for intimate stories that tackle politically engaging and timely cultural issues. It’s made her job more challenging — often she must slog through thousands of hours of footage to search for the beats and characters that push the narrative forward. But, ultimately, it’s created a rewarding career.

Her instincts were likely what caught the attention of Julia Reichert, one of the top documentary directors working today. Since 1971, Reichert has made feature-length documentaries that embrace tough subjects: socialism, feminism, unionization, and radical action. They’re noted for their compassion and empathy, portraying complex political stories through the lens of ordinary people.

No surprise, then, that Jonathan Olshefski’s documentary Quest (2017), an Utz-edited intimate portrait of the daily struggles of an African-American family living in Philadelphia, caught Reichert’s eye. Indeed, Quest, a nominee in two Emmy categories this year, has already netted Utz a Cinema Eye prize for Outstanding Editing.

Given the recognition Utz is receiving from all quarters, Reichert’s decision to approach her about American Factory makes a lot of sense. Utz, deeply committed to verité craft and stories with substance, was immediately interested in the project.

It’s choices like these that are putting Utz at the forefront of her game. She’s served on the jury of tier-one documentary film festivals, such as 2018’s Full Frame. And earlier this year she was asked to join the Academy of Motion Pictures’ documentary branch, a responsibility that’ll mean watching up to 200 documentaries each year to help choose the nominees for best documentary in both the feature and short categories.

While American Factory is the first film to be released through the Obamas’ Netflix-partnered Higher Ground Productions, it won’t be the first time a documentary edited by Utz is receiving early whispers among Academy members. Her first film, Bully, was shortlisted for an Oscar after premiering at the Tribeca Film Festival.

Journalist Elaisha Stokes, herself a documentary filmmaker, sat down with Utz before American Factory’s release to talk about what it takes to get through such a monumental edit. (more…)

A few days before we shot Father Figurine, I sat down for an interview with Austen, who was helping shoot the behind-the-scenes video for Shift, and he asked how it felt to prep a movie so quickly after spending so much time writing the script. Austen was trying to get at the idea that once you actually go and make the thing, it suddenly becomes this huge crunch, but I genuinely didn’t feel that way about pre-production. Sure, there was lots of work to be done, but once we got the grant, we had about three months to prep the project, which was more than enough time for a short, and I rarely felt rushed.

(more…)

Producers Brendan and Garrett Christian Hall look on at director Jonathan Langager during the Shift Showcase.

As the inaugural year of the Shift Creative Fund drew to a close, we celebrated the first cohort at a showcase earlier this year. The four filmmakers who received grants (and the crews who produced their works — filmmaking, after all, is deeply collaborative) generously joined us on stage to reflect on their films and the lessons they walked away with at the end of the productions. It was an eye-opening conversation worth sharing with other creators; let’s find out what they had to say.

(more…)

Learn more about connecting MediaSilo with Zapier.

User productivity is our #1 goal here at MediaSilo. That’s why we built a Zapier integration for our flagship platform: to let you build custom workflows from the thousands of apps available on the Zapier marketplace.

Did You Know?

Zapier creates “webhooks,” simple integrations that send information from one place to another. For example, when you sign up for flight notifications on your phone, your airline uses a webhook to transmit information from its system to the SMS provider.

Apply the same idea to MediaSilo — you could be notified whenever changes are made in the system in ways that are most convenient for you.

Below are the three most popular ways our customers use Zapier to amp up their MediaSilo workflow. They’re all time-savers that are quick and simple to set up. You might just want to add one (or more) to your toolkit.

Warner Bros. recently trolled Pokémon fans with a fake leak of Detective Pikachu, which turned out to be a 100-minute video of Pikachu dancing. Jokes aside, content leaks represent huge costs to media properties in both clean-up and lost revenue, and a large portion of them come from seemingly mundane scenarios.

Like when Mr. Bigshot Film Critic shares his screener password with his wife who then shares it with her — oops! — book club or when the VP of marketing at XYZ Studios leaves her iPad unlocked, giving her kids access to share, say, the final episode of TV’s most popular show ever.

When it comes to pre-release content, all kinds of people representing all levels of tech and security savvy may have access to your most important content. A network may be sharing show previews with press reviewers, predominantly TV, film, and cultural critics. Authorized viewers might also include VIPs such as writers, directors, and actors; an external post-production or marketing team; and internal team members tasked with sharing the content. A single mundane mishap can cause problems that range from damaged media properties to very costly clean-up.

Good news is most leaks can be prevented with a few simple measures, but when a leak happens, you’ll first need to trace the sequence of events, including who shared the content and how. Start by asking these three questions:

What’s the content?

Is it cultish or nerdy with a strong fanbase? Does it have a highly anticipated reveal? Has it been well marketed? If you answer yes to any of these, chances are someone out there likes the content and thinks everyone should see it right away.

What controls were in place when the content owner shared it?

Did they lower their guard either accidentally or on purpose? Why did they lower their guard? Were they, for instance, helping an executive log in who forgot her password? Or was it something else? Typically, they’re trying to reduce friction for someone they trust to access the content.

How did the authorized user lose custody of the content?

Was it shared on purpose or by accident? With or without their knowledge? Authorized users don’t usually pirate content directly. In fact, they sometimes share it on purpose, which leads to the first threat: oversharing.

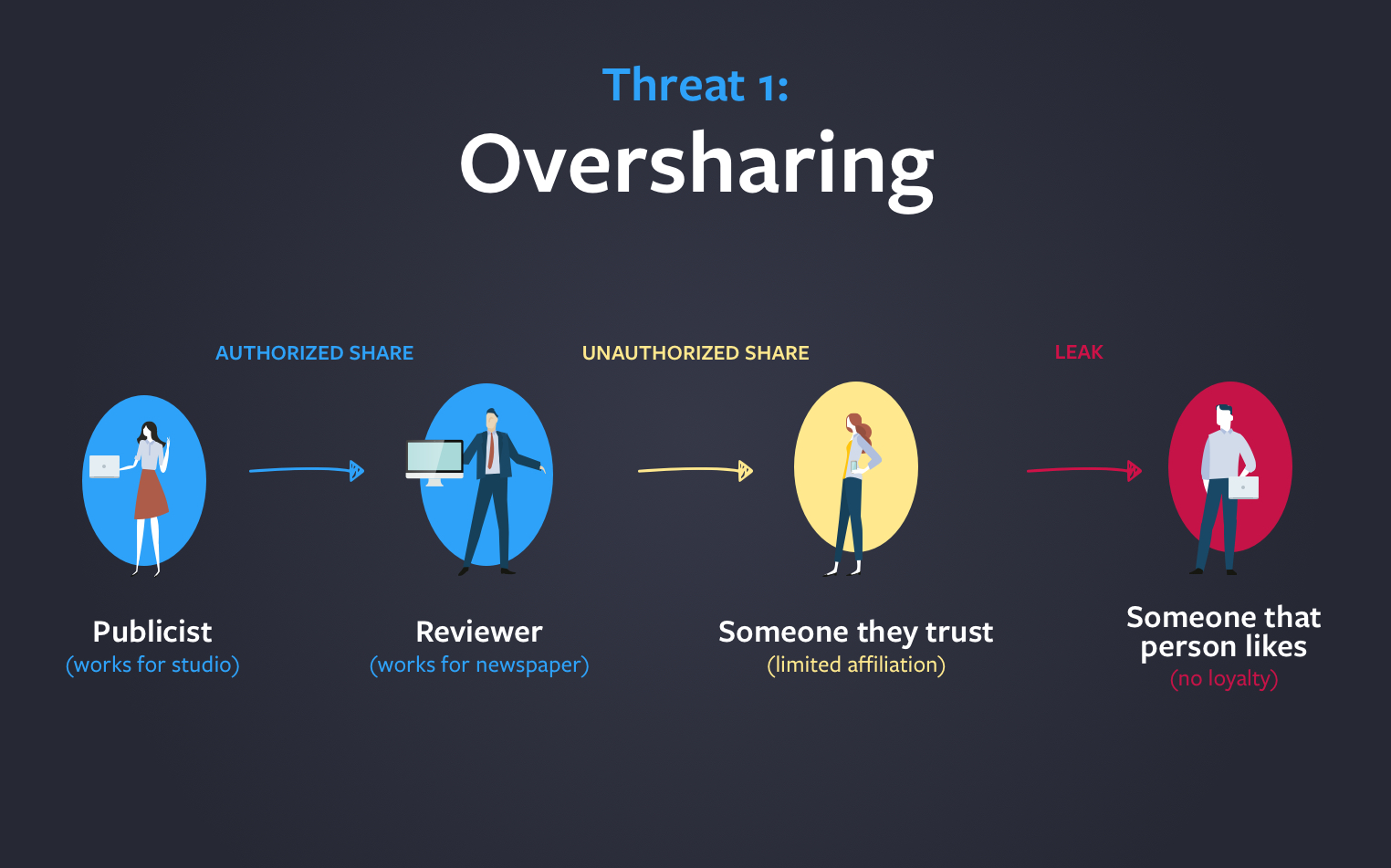

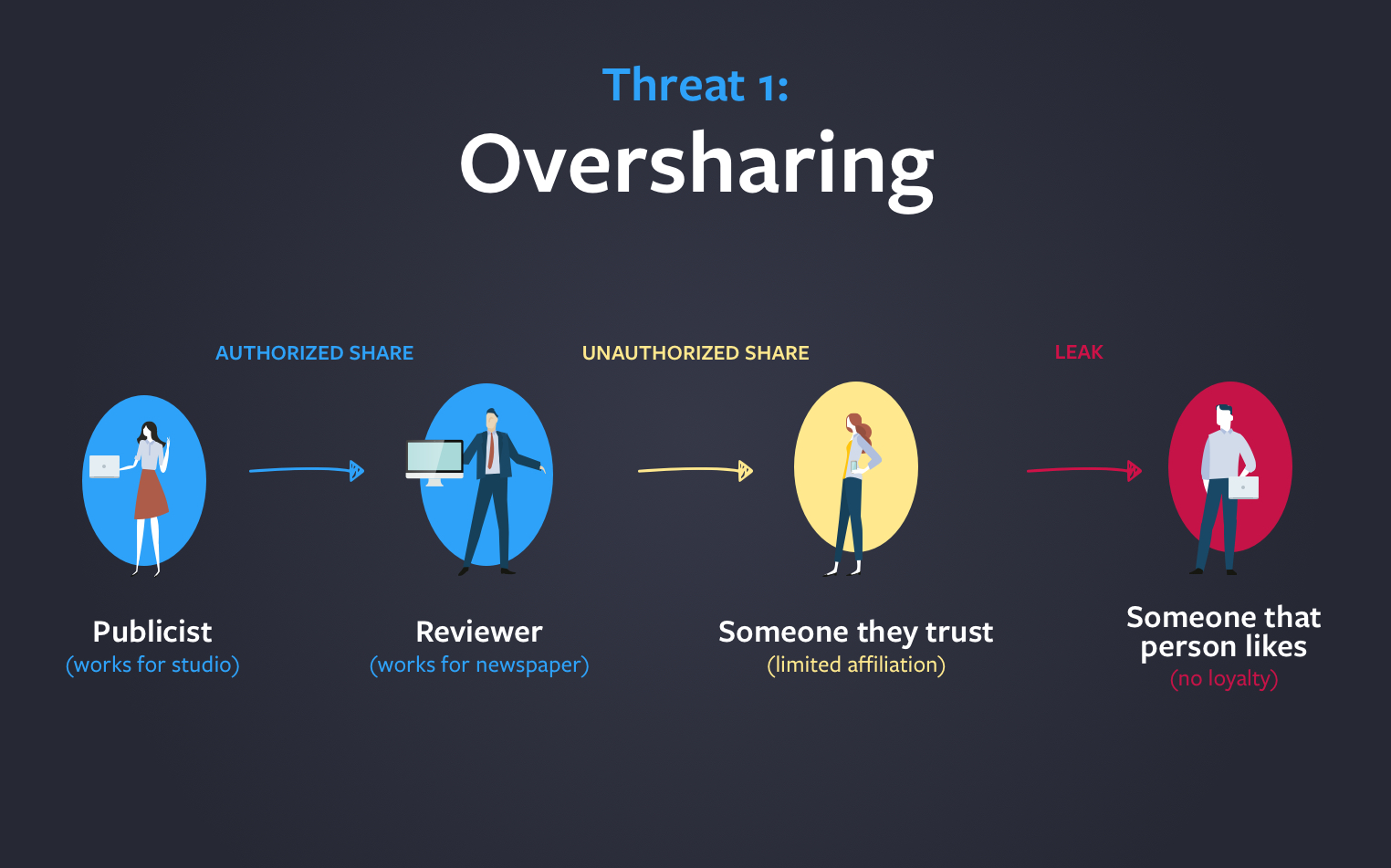

Threat #1: Oversharing or “The Lover Threat”

Who else in your life knows at least one password you use whether it’s for your laptop or email? At least one person — your partner, family member, or BFF — likely has access to your digital assets. Often where there’s a relationship in place (romantic or otherwise), there’s a risk that the authorized user will intentionally share access with an unauthorized user. We call this “The Lover Threat.”

Here’s how it might happen. Let’s say you’re a TV critic who got a screener of a pilot from a network’s PR firm. You share it with your boo, thinking you’ll change the password to the screener later. That person probably doesn’t pose a threat, but what if he shares it with someone else who has no loyalty to you?

Or maybe you forward the email invitation to the screener, and whoever receives it — can you really control who does or doesn’t? — downloads, rips, or shares the file? Things can get hairy fast.

When you’re searching for a software solution to these issues, be sure that it includes the following security measures.

The best antidote to passwords? No passwords at all. Systems that use an email verification process like Magic Link ensure that the content is only accessible through the reviewer’s email, so there’s no longer a password to forward or share.

- Multifactor Authentication (MFA)

Since email can be compromised and passwords shared, content owners should be able to turn on MFA as an additional layer of protection. Multifactor involves authenticating your identity with a code from a third-party application like Authy or Google Auth, typically on your smartphone. The downside to MFA is that it adds an extra step to login and can be troublesome if you lose your phone, which is why we also recommend alternatives like biometrics and physical security key, which we discuss below.

Visible watermarking takes the form of a personalized watermark burned onto a video file the moment a viewer presses play. The authorized viewer’s name and email immediately appear on the video player, communicating that the viewer is, in some ways, also being watched.

In addition to the visible layer, you can find software like our own SafeStream that includes an invisible watermarking system that can help analyze and track down the leaky workflow and user.

- Digital Rights Management (DRM)

DRM is a set of technologies that allows content owners to issue time-limited licenses to content and offer enhanced security. It locks down the player, which makes ripping the video harder.

We recommend that all networks and content owners ask reviewers to sign nondisclosure agreements (NDAs) and other legally binding contracts and to train them how not to share content.

With these features in place, it becomes much harder for users to share content, accidentally or otherwise.

At Shift Media, we include all of these security measures in Screeners.com, a screening app for networks to share pre-release content with a variety of viewers.

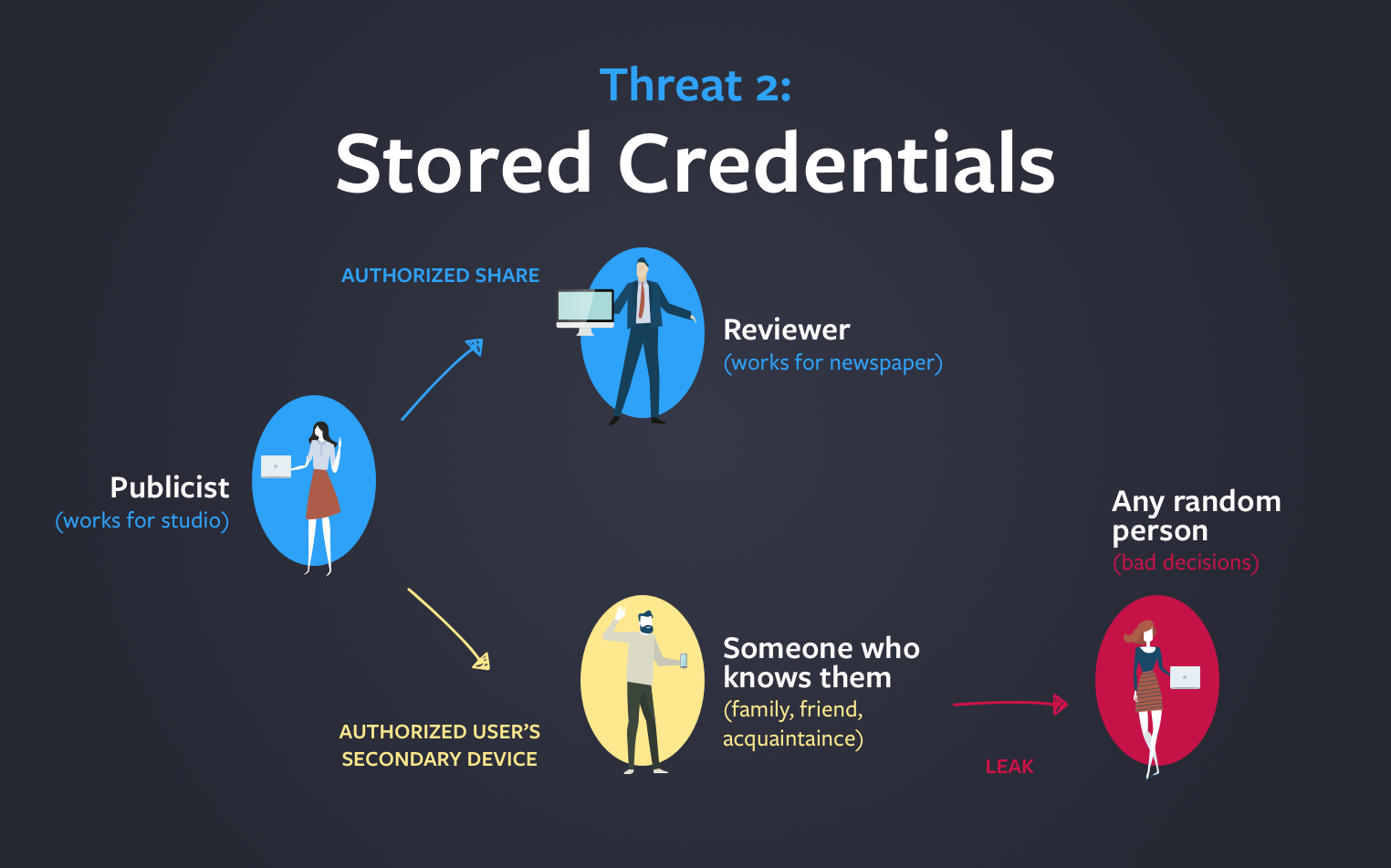

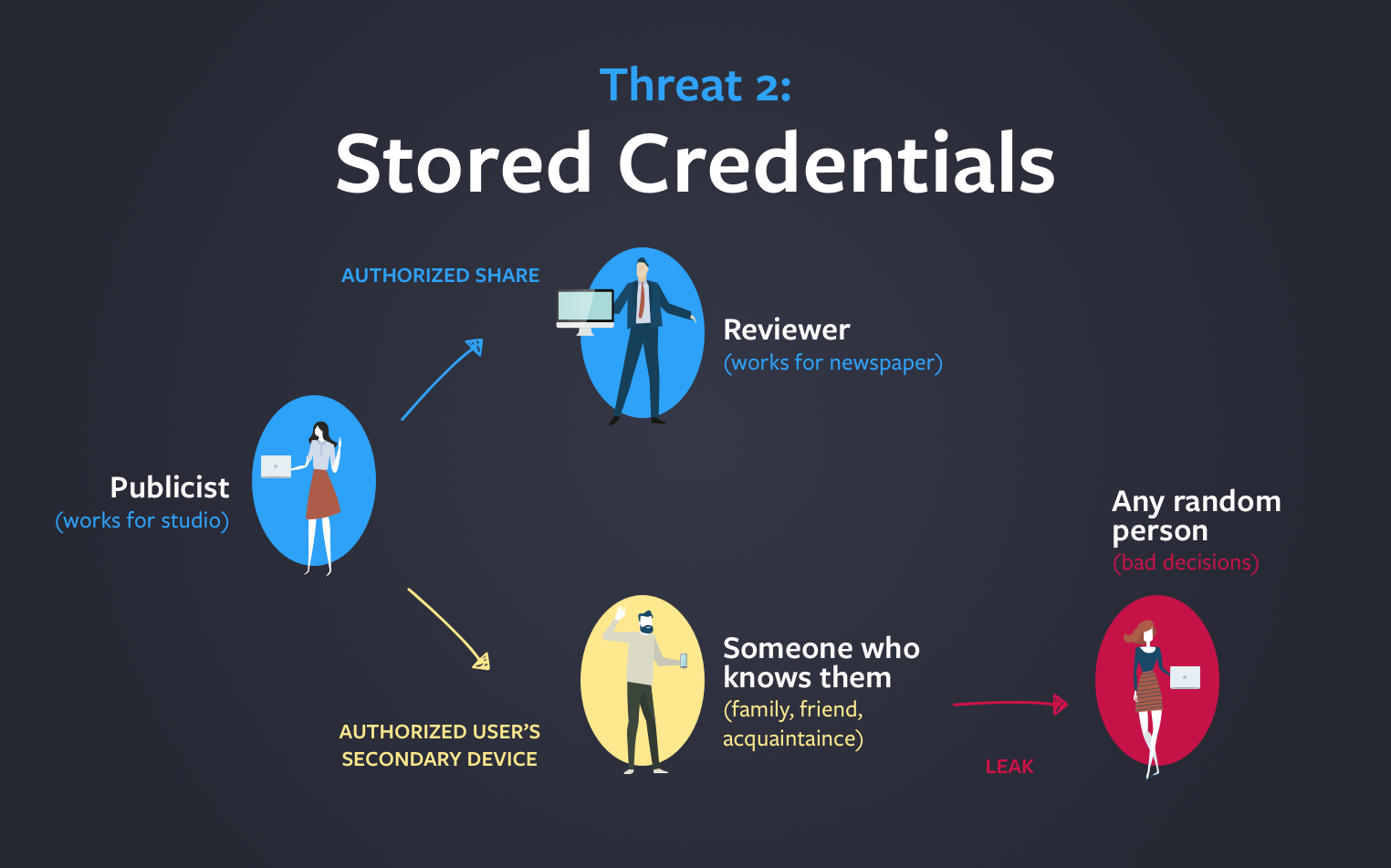

Threat #2: Stored Credentials or “The Open iPad”

One threat has recently worsened and is more common than we realized: when an unauthorized user has standing access or can gain access to an authorized user’s credentials. We call this “The Open iPad” because devices save passwords that people reuse and share, and family and friends often know each other’s password habits and four- to six-digit passcodes.

In the scenario shown above, a network’s publicist may not know that the reviewer has a secondary device with direct access to the content or indirectly through email. Anyone who knows how to get into the device can break in and leak its content.

Here, Magic Link directly addresses the password-storing and sharing issue — no more passwords! MFA also helps in this situation as long as the authenticator app also isn’t registered on the same device. At Shift Media, we prefer to register the device and to expire that registration in a number of days or weeks. Otherwise, the device becomes stale, so to speak, and others can gain easy access.

Again, visible watermarking reminds the potential leaker who the iPad belongs to, which may give them pause. It also forces the leaker to put in the work of anonymizing the watermark, while forensic watermarks help track down the leaky workflow and user. DRM further complicates the downloading and ripping process.

Threat #3: Account compromise

The last everyday threat is when an unauthorized user compromises the email or system account of an authorized user. The attacker has no loyalty to the authorized user and either phished them or compromised their email or system account.

The general public is becoming more aware of the controls available against email compromise, but phishing and compromise accounts are still quite common. MFA remains today’s best defense against such compromises, but MFA can be problematic. At Shift Media, we’re looking at biometrics and physical factors as the next frontiers.

Studios and production companies deal with close proximity issues such as people trying to get on set — by faking identities, for instance — and these people might try to defeat endpoint controls, though probably not by spoofing fingerprints. However, when it comes to sharing pre-release content, proximity is less of a concern. We’re more worried about securing web and mobile software, so biometrics and physical factor protections are very useful.

For instance, iPhone users are probably familiar with TouchID, FaceID, and Face Unlock. All require a body part — finger, face — to unlock, but because those are individual to the iPhone owner, access can’t be shared widely and, beyond an unlikely horror movie-like scenario involving severed fingers and other grim possibilities, can’t be stolen. Availability and quality of biometric protections varies, where mobile (and particularly iOS) has a strong product, so we’re now waiting for the rest of the industry to catch up.

As for physical security, we like YubiKeys on the U2F standard, a USB device that plugs into laptops. The physicality of YubiKey makes it difficult to steal beyond a shared device and outside of one’s immediate social circle. Availability varies, so having both protections are important — biometrics where available on mobile and personal devices and physical security keys on everything else.

Besides these solutions, you can also use a watchmen service to monitor anomalous activity. These activities include users on too many devices in too many different locations, accessing content from odd locations, simultaneous viewing from multiple devices, watching more than twenty-four hours of content in a day, and watching the same content twice from two devices on the same account.

When it comes to security for Screeners.com, we’ve focused our attention on improving detection and responses to these particular scenarios, which we see as the most common sources of our customers’ leaks. Our approach to content protection was born out of several decades of experience developing and maintaining other Shift Media products: MediaSilo, a content-sharing platform and lightweight cloud DAM, as well as Wiredrive, a cloud content library with presentation workflows.

All to say, we’re seasoned experts who’ve observed the pitfalls that our customers and others in the industry regularly encounter. The notes we’ve shared here result from decades of experience, and we hope they prove helpful in protecting the content you’ve worked so hard to create.

Women’s History Month has come and gone, but we think putting a spotlight on women for a scant thirty-one days out of 365 is super bogus, kinda like the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences’ attempt to sideline editing at this year’s Oscars.

With that firing us up, we transformed our irritations into a post that celebrates editing and women, who edited just 23 percent of top 500 box office titles in 2018. They haven’t necessarily gained much ground since 2016, either: The ratio of white male editors to their underrepresented women counterparts has remained 58.8-to-1, which is ironic, given that film editing was one of the first jobs available to women in the industry. It was originally considered remedial work to splice reels together, and men only got involved once editing proved to be such an essential (and lucrative) practice.

So, as we strive for a more equitable future in the film and TV industries, it’s important to look at the women who paved the way, as well as those who are blazing a trail for the women yet to come.

Margaret Booth

Perhaps the grandmother of the field, Margaret Booth helped launch editing as a profession. She was initially considered a “patcher,” or film joiner, for D.W. Griffith, as she worked to make ends meet after her brother died in a car accident. By 1924, such experimental cutting-room work secured her a job at Louis B. Mayer’s studio, which later merged with Metro-Goldwyn to form MGM. Producer Irving Thalberg allegedly coined the term “film editor” as a proper hat-tip to Booth’s skills, and she eventually became the studio’s supervising editor. She received an honorary Oscar in 1978 and edited her last movie not long after with 1982’s Annie. Booth died at the age of 104 in 2002.

Verna Fields

A prolific editor of smaller-scale projects through the 50s and 60s, Verna Fields started mentoring film students at the University of Southern California and funneling them into Hollywood. Nascent director Steven Spielberg tapped her to edit Jaws in 1975, with Fields’ contributions helping launch the first-ever summer blockbuster. Christened “Mother Cutter,” she was hired as vice president of feature productions at Universal Studios and became one of the first female executives in the industry. Her editing credits further included Paper Moon, Medium Cool, American Graffiti, and Daisy Miller. Fields was honored with the Women in Film Crystal Award in 1981, one year before her death.

Dede Allen

Dede Allen’s career endured almost as long as did Booth’s. Born in 1923, she changed the editing and pacing of Hollywood films with her use of the jump cut, as well as a European staccato style and overlapping sound techniques. Allen was nominated for three Academy Awards, but her signature moment may still be the dramatic ending ambush of Bonnie and Clyde in 1967. Using about 50 cuts in a minute, Allen delivered audiences a thrilling and innovative conclusion. “It’s a very exciting profession because you really get to play other characters. You get into a story, and that story becomes real to you,” she told NPR. “I suppose it’s like an escape.” Allen was honored in 1994 with the American Cinema Editors Career Achievement Award. She passed away in 2010.

Barbara Hammer

Another trailblazer in the field, Barbara Hammer championed cinema for the LGBTQ communities. Her avant garde, often-challenging works touched on menstruation, lesbianism, sex, and feminist theory. Her signature title, 1974’s Dyketactics, deployed more than 100 shots in a span of four minutes and left critics stunned. Hammer was dedicated to producing work that avoided the masculine gaze, and she joined advocacy efforts during the AIDS crisis. She died this year at the age of seventy-nine.

Thelma Schoonmaker

Born just one year after Hammer, three-time Oscar-winning editor Thelma Schoonmaker was honored with a BAFTA Fellowship earlier in 2019. It’s a stunning coronation of a long journey: The Algerian-born Schoonmaker endeared herself to Martin Scorsese at an NYU film study program and helped salvage some botched cutting work on his 1963 title, What’s a Nice Girl Like You Doing in a Place Like This? Nevertheless, Schoonmaker originally struggled to meet the criteria for the editors union in the 1970s, and her career stalled as a result. Her first Oscar nomination came in 1971 for Woodstock; her three wins were for Raging Bull, The Aviator, and The Departed. Schoonmaker works with Scorsese to this day and is listed as the editor of his forthcoming film, The Irishman. “I think the women have a particular ability to work with strong directors,” she once said. “They can collaborate. Maybe there’s less of an ego battle.”

Born just one year after Hammer, three-time Oscar-winning editor Thelma Schoonmaker was honored with a BAFTA Fellowship earlier in 2019. It’s a stunning coronation of a long journey: The Algerian-born Schoonmaker endeared herself to Martin Scorsese at an NYU film study program and helped salvage some botched cutting work on his 1963 title, What’s a Nice Girl Like You Doing in a Place Like This? Nevertheless, Schoonmaker originally struggled to meet the criteria for the editors union in the 1970s, and her career stalled as a result. Her first Oscar nomination came in 1971 for Woodstock; her three wins were for Raging Bull, The Aviator, and The Departed. Schoonmaker works with Scorsese to this day and is listed as the editor of his forthcoming film, The Irishman. “I think the women have a particular ability to work with strong directors,” she once said. “They can collaborate. Maybe there’s less of an ego battle.”

Marcia Lucas

Marcia Lou Griffin was an ambitious commercial editor and a student at USC’s film school when she met her first husband, George Lucas. She then edited The Rain People and American Graffiti — and was Martin Scorsese’s go-to supervising editor for his first studio movies — before helping Lucas write the first drafts of Star Wars. Her work was finally recognized with an Oscar at the 50th Academy Awards. Marcia’s contributions to the massive franchise run deep: She famously warned George, “If the audience doesn’t cheer when Han Solo comes in at the last second in the Millennium Falcon . . . the picture doesn’t work.”

Margaret Sixel

Born in South Africa and educated in Australia, Margaret Sixel pulled off a herculean effort in editing husband George Miller’s Mad Max: Fury Road. Due to the number of cameras and the intense vehicular stunts involved, she was required to compress more than 470 hours of footage into a two-hour masterpiece. She was recognized with BAFTA and Academy Award wins, and Fury Road resonated with action-flick fans and feminist audiences alike. It may be her magnum opus to date, but Sixel has also edited more whimsical works like Happy Feet and Babe: Pig in the City and was involved in a string of Australian advocacy documentaries in the late 90s.

Mary Jo Markey + Maryann Brandon

Two more contemporaries worth celebrating: Mary Jo Markey and Maryann Brandon. A team that linked up while working on J.J. Abrams’ Alias, Markey and Brandon share an eclectic filmography that ranges from the show Lost to the movies Mission Impossible III and The Perks of Being a Wallflower. Together they’ve taken on portraying the depths of space, first with 2009’s Star Trek and then Star Wars: The Force Awakens in 2015. Their creative chemistry is palpable, and they shared an Academy Award nomination for the latter film. Brandon is even leading the editing process of this year’s anticipated Star Wars: Episode IX.

Joi McMillon

Exemplifying the strides women are slowly but steadily making in editing, Joi McMillon stands out as the first black woman ever nominated for an editing Oscar for her work with Moonlight. She’s already become a trusted confidant of director Barry Jenkins, having known him since she was a student in film school, and her filmography includes If Beale Street Could Talk, Lemon, and the forthcoming Zola. Before such prestigious works, she edited TV comedies and reality shows. “I think a lot of people have seen the need to be more diverse,” she told Blackfilm recently. “Listen to that call. Be conscious of adding more diversity in the cutting rooms.”

Writer-director Yen Tan recently emailed to tell me Ciao, the movie we made in 2008, had been posted to YouTube — illegally. A fan in Brazil had uploaded it, and it already had more than 2 million views. I didn’t know whether to be angry or impressed.Unfortunately, if you’re a content creator, you’re eventually going to run into this very situation. You post content you made, and whether out of admiration, ignorance, or greed, someone else rips and reposts it. Having your work severed from your carefully thought-out distribution plan leaves you, the creator, with fewer views, fewer shares, and — if you’ve monetized the video — less profit.

When that day comes and you’re the victim of piracy, here’s what you can do.

Are you the copyright owner?

Keith Kupferschmid, CEO of Copyright Alliance, a nonprofit that protects content creators and organizations through copyright advocacy, first suggests making sure you actually own the copyright.

“If you’re not the copyright owner, you are very much restricted in terms of what actions you can take,” he says. “So, if for some reason, you’ve assigned your rights to the content to somebody else, you really don’t have the right to say, ‘Hey, take it down.’”

For instance, if you’re employed as work-for-hire, then the copyright belongs to your employer, not you. Another example? If you licensed your completed work, the copyright may transfer to the licensor for the length of the agreement. But if you were the original author of the work and didn’t assign or transfer the ownership of that copyright to someone else, it’s likely that you own the copyright.

There’s an exception to copyright law, though. Called the “fair use doctrine,” it allows for the use of copyrighted work “for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching, scholarship, or research,” according to Copyright Alliance. That said, if the entirety of your work has been reposted without your permission, it’s almost certainly not protected under fair use.

So . . . congrats! Your work just got pirated.

Where does the material appear?

If you are indeed the copyright owner, where you go after discovering your pirated work depends on where it’s been posted. Is it on social media or a video-sharing platform like YouTube, Facebook, Vimeo, Twitter, or other website where users can upload their own content? Or is it on a website where the content has been curated and published by the site owners?

If it’s the latter, you should first reach out to the webmaster directly to tell them you own the copyright and don’t want them using it. That’s usually enough to get the average offender to take down the infringing material.

But let’s say you instead find your pirated work on social media or a video-sharing platform, where a user has uploaded the infringing material.

Says Andrew Hutcheson, co-owner of Voyager, a production company working in the branded documentary and commercial space, “We got very fortunate to have one particular film called Junk Mail blow up on Vimeo. It got around 8 million views, and we got a lot of press for it online.”

A few months later, he started seeing links to what looked like his film. “I clicked on a video that had 15 million hits. It was just a rip of our piece that was put up there,” says Hutcheson. “Then I Googled, wondering if there was anything else up there, and I found three or four pages worth of uploads.”

Here where the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) comes in.

Filing a DMCA takedown notice

In 1998, Congress passed the DMCA, a comprehensive set of laws that address online copyright infringement while attempting to balance the needs of users, creators, and service providers. One provision — the “Notice and Takedown Process” — is the most common way content creators can address the illegal use of their work online.

All of the major social media and video-sharing sites have a similar process for notifying them that your copyrighted work has been uploaded to their site without your permission.

Let’s use YouTube as an example.

To submit a takedown notice, you’ll need to go to the video on YouTube and flag it as infringing on your copyright. After you’ve identified by offending work, you’ll have to electronically swear under penalty of perjury that you believe the video is an infringement and likely doesn’t fall under a fair use exception.

Once you’ve filed the notice, YouTube sends your complaint to the offending user, who then has the opportunity to file a counter notice if they feel they have a legal right to the material. If they refuse to take it down, your only way forward is to sue in federal court.

Pirates gonna pirate

The DMCA establishes federal court as the jurisdiction for all Internet copyright issues, even when there’s only a few hundred dollars at stake. “On average, it costs $350,000 to bring a copyright infringement case in federal court,” Kupferschmid says. “At this point, you have to ask yourself how much this really means to you.”

If you’re a big studio with a billion dollars at stake over leaked content, it might make sense to spend a few hundred thousand to protect your profits. For most indie creators, however, it just isn’t worth the time and expense to sue.

“On average, it costs $350,000 to bring a copyright infringement case in federal court . . At this point, you have to ask yourself how much this really means to you.”

Fortunately, says Kupferschmid, “it’s pretty rare for somebody to push back.” The vast majority of infringing material is removed upon receipt of a takedown notice.

Automated copyright protection

Sometimes, though, you might find your work reposted, often by the same person on the same platform. Because both legal and illegal videos are monetized based on the number of views of the content (and the ads attached to it), there’s little incentive for pirates to spend time and money fighting a takedown notice.

Instead, they can repost the stolen material under a different name, immediately restarting their illicit monetization and putting the onus back on you, the copyright owner, to discover the piracy yet again and file another takedown notice.

“Notice sending is a good way to get the content down, but once the cat’s out of the bag, it becomes very difficult to contain it,” says Janice Pearson, VP of global content protection at Convergent Risks, which consults on security, risk, compliance, and technology solutions for studios, distributors, and M&E vendors. “To help, typically you hire third parties who’ll crawl the Internet to see if your content comes up on YouTube and other sites to send automated takedown notices on your behalf.”

Several companies are developing a technology called Automatic Content Recognition (ACR) that partners with audio- and video-sharing sites to identify copyrighted material and prevent it from being uploaded.

YouTube, for example, has been at work on proprietary ACR software that, for now, is available only to major content producers who can afford to have their videos digitally fingerprinted.

Most other sites partner with Audible Magic. Independent artists can register their work for free with the company, providing an added layer of protection across most of major platforms, including Facebook, SoundCloud, Twitch, and Vimeo.

The downside to ACR is that legit users can get caught up in it. Hutcheson says it’s been a nagging issue for music-video directors who have permission to use the video for their own professional promotion, but because the record labels are using ACR to protect the music track, the videos also get flagged and taken down. Worse yet, “if you have a couple of those happen, your account is suspended, [even though] the people who directed the video have the right and permission to use it,” he says.

Strategies moving forward

At the end of the day, if you’re uploading your work to a public site, it’s nearly impossible to keep your work from being ripped and reposted. The best you can do is stay vigilant.

Hutcheson creates Google alerts “of the names of our projects, our directors, how they correlate, and instances where they’re used together.” He also schedules recurring tasks in his calendar so that he checks the major sites every few months. “Every time I do it, I find stuff I have to pull down. Every single time,” he says.

Kupferschmid acknowledges the system is far from perfect: “We play this game of Whack-A-Mole. You get it taken down, and it’s back up. It’s really not an efficient or effective process. But that’s the process unfortunately. At least for the time being.”

What does all of this mean for my film? Well, I notified our distributor that the film is up on YouTube, and as of this writing, it’s still online, with 2,074,481 views and counting.

Update: Looks like my movie Ciao is no longer on YouTube. The process worked! (For now at least.)

Rounding out the first installment of posts from the inaugural cohort of our Shift Creative Fund, producer Christian Hall provides a detailed account of the pre-production and production process for Cosmic Fling, a truly unique short film that fuses miniature sets, marionette puppets, and live actors. Together with director Jonathan Langager and their crew of talented puppeteers, VFX coordinators, and more, the team made it through an intensive three-day shoot that required a total of 100+ shots. Let’s find out how they prepped for success.

Cosmic Fling is a story of resilience in the pursuit of love. Stan, its protagonist, is the sole resident of a desolate moon, a cosmic garbageman who harpoons space debris and dumps it into a crater. One day, a comet whizzes by, and he sees a beautiful astronaut — Beatrice — looking back at him. Her comet shoots across the sky and disappears, returning periodically to zoom past again. Stan devises a plan to spear it and tether it to the cold rock he calls home. He and Beatrice will then climb across the vastness of space to meet.

For my and Jonathan’s story, the journey from script to screen has spanned more than six years. Two other attempts to make Cosmic Fling fell short, but as a testament to our own resilience, we persevered with partnerships, adding the Shift Creative Fund to our list of collaborators.

Giving credit where it’s due

But, for principal photography, you need a solid team of talented, highly skilled, and generous filmmakers. Cosmic Fling writer and director Jonathan Langager and I met in 2012 at the University of Southern California, where we worked on his thesis film Josephine and the Roach. I was developing an optical motion capture software and required use cases for consumers, and that’s how Cosmic Fling was born. We thought we’d use CG paired with motion-capture animation, but time constraints kept us from getting the film off the ground. Jonathan and I stayed excited about it, but years passed, and it wasn’t until we gave the script to Taylor Bibat, a producer at Fonco Studios, that using marionettes for Cosmic Fling instead of CG was proposed.

We began working with Sam Koji Hale, producer at Handmade Puppet Dreams and director of Yamasong, to bring the story of Stan, our intergalactic garbageman, to life. First, Sam provided sketches of Stan, then came the actual puppet, which had to be dressed, painted, and outfitted with the many components of Stan’s spacesuit. Some elements were built to deliver an on-screen effect, such as the button on Stan’s Waste-to-Nutrient Conversion Unit, which he needed to be able to push on his forearm. Out of it would pour sludge made from color-dyed oatmeal, but during production, we found that even the simplest of Stan’s movements — lifting and aiming his harpoon, for instance — proved maddeningly complex to perform. Marionettes are delicate and highly tuned instruments capable of sublime performances, but we needed an expert.

Producer and director Sam Koji Hale adds finishing touches to marionette Stan.

Luckily, we were able to bring in master marionettist Phillip Huber (Being John Malkovich, Oz the Great and Powerful). When Phillip took Stan in his hands, a new connection was formed, and our lead character came to life. Phillip and Jonathan practiced Stan’s movements — everything from aiming the harpoon gun to dancing in space — before the shoot. Seeing this firsthand as I did was an eye-opening gift.

My gratitude extends to Fon Davis, our production designer. Previously with ILM, he’s worked on such films as The Nightmare Before Christmas, the Star Wars prequels, Coraline, and projects such as the Disney Channel’s Penelope in the Treehouse and Eliza Rickman’s Pretty Little Head music video, which we collaborated on together. We used Fonco, his studio in Los Angeles, for the shoot and for designing, fabricating, and preparing our set pieces. Fon’s team of artists created the surface of the asteroid you see in Cosmic Fling, as well as the space debris and miniature versions of the asteroid and comet.

The calm before the storm

The film draws from a slew of filmmaking techniques, so preparation was complicated. Take, for example, the use of green screen to replace the background with a star field. Screen tests helped us decide if a practical star field using matte painting or cloth with light would achieve the effect we were going for. Jonathan and I prefer working with as many in-camera solutions as possible as opposed to relying exclusively on CG and digital FX. We love the filmmaking process and have an affinity for movies that use creative, in-camera techniques to build a unique world and inspire audiences to wonder how it was made. Cosmic Fling is no different: We combine actors Josh Fadem and Caitlin McGee’s live-action performances and composite them into the visors of our characters’ space helmets.

That said, budgetary and post-production parameters naturally played a role in our decisions. For example, using a painted star field would seemingly reduce VFX resources, but that’d mean contending with multiple strings from the marionettes. Even using minimal microfilament strings — which reflect a lot of light — during a screen test, the decision was clear. Without a green screen, it’d be more of a burden to digitally enhance or remove strings, as well as inadvertently draw attention to the strings interacting with the star field background. We knew from the get-go, though, that VFX would play a huge part in production, which would include set extensions, rotoscoping, animation, and numerous plate shots and inserts. To help us think through the process, we had conversations early on with VFX consultants and specialists.

In fact, it was the wisdom and genius of resident rock star Tim Hendrix — as on-set VFX supervisor — that guided us during production. He answered questions throughout the shoot, patiently listening as we wondered whether Stan’s helmet light should be on during certain shots or if our puppeteers should wear green suits in others. Tim understood which tasks would be easy in post-production and which wouldn’t. Joined by our primary VFX supervisor Ben Kadie, we developed a plan before shooting to address the impacts of VFX on 100+ shots in our film.

The shoot

Given that many shots over a three-day period, we worked carefully with assistant director Lily Zeigler to come up with a shooting schedule based on lighting set-up and the needs of our miniature asteroid set. Typically, we’d sort shots by location to limit the number of company moves and then by time of day or what light would be available or necessary. Lastly, we’d organize shots by coverage or type, e.g., extreme wides to close-ups.

But for Cosmic Fling, marionettes were our stars, and we had a controlled sound stage and MOS environment for the entirety of the production, so we didn’t have the same kinds of constraints. Jonathan worked closely with Damian Horan, our director of photography, using the storyboards as a guide for each scene. We also had a dolly to bring movement to the shots, while the confined space of the miniature environment — Stan’s asteroid was built as a 8 ft x 12 ft surface and included his makeshift billboard home and lots of craters — allowed for intricate adjustments to the lighting set-up.

A matter of time

With time as your most valuable resource during principle photography, finishing 30+ shots per days is ambitious, especially with puppets. They involve so many unique factors, such as restringing marionettes for certain movements, replacing broken strings, and keeping strings away from the faces of Stan and Beatrice to limit rotoscoping. Performance-related variables, such as how the characters would dance together or climb ropes, also played a role.

Marionettist Phillip Huber inspects the miniature set as the crew looks on.

We anticipated some of these factors ahead of time, while others presented themselves on set. Controlling the wobble of Stan’s helmet, for example, required ongoing adjustments throughout the shoot. And Phillip, who we outfitted with a monitor so he could see his performance and respond more quickly to direction, did all he could to control the motion of the puppets. At the end of the day, though, they’re puppets. Total control of their movements is elusive.

Given these constant adjustments, there was very little time to spare, and Damian and his grip and electric team worked tirelessly to create the right lighting set-up for each shot. Lily negotiated the time for each, working closely with Jonathan and Damian to keep our schedule on track and brokering which additional takes we could or could not accomplish due to time constraints.

Meanwhile, Kat Roberts of Fonco Creative fabricated, painted, and dressed the many miniatures that made up Stan’s world. There were many distinct pieces of space debris that cluttered his asteroid set, including a bathtub and oil barrels. Each scene called for a slightly different configuration of Stan’s environment, such as various miniature billboard homes, to reflect the passage of time. And, because we shot out of sequence, Lily and the team kept a close eye on maintaining continuity. Some of the billboards were filmed clean, then used as backdrops for Stan’s day marks. We had a limited number of takes to film Stan marking the billboard in medium and insert shots.

One of the most complex sequences to film was Stan and Beatrice dancing in space. Even after rehearsing, swapping strings between our puppeteers in a confined lighting arrangement was challenging. We filmed that sequence on the last shoot day, and while it was difficult, nailing it was extremely rewarding. Jonathan played music to set the mood for each take, making Stan and Beatrice feel more alive than ever.

Matt Kazman, screenwriter for short film “Father Figurine, ” waves hello.

Matt Kazman, screenwriter for short film “Father Figurine, ” waves hello.

When we launched the Shift Creative Fund, we didn’t know what would come through the transom, like a film featuring a stuffed corpse. Which is what we got with Matt Kazman’s Father Figurine. The odd, hilarious, and touching script drew the judges in, and now here we are, reading about the making of the film, one of three selected among hundreds of applicants.

Screenwriter Matt Kazman sent us a dispatch on the pre-production process, and we’re sharing it here to give aspiring filmmakers a sense of what’s involved in moving from concept to screen. Matt provides wise insight that all moviemakers — all creators, really — would be smart to heed. See what we mean below.

Being in pre-production is a reminder of all the things I love and don’t love about filmmaking. I love having creative conversations with everyone about how to bring this crazy idea to life, because they bring their own ideas, and a lot of them are really great, and suddenly, this vision you had develops into something much more cohesive, detailed, funny, and resonant.

I might be reaching with that last one, but the point is: A movie becomes much better when you start working with others than it ever was when you were, like, writing alone in your “home office” (read: a desk in your living room). Collaboration is something I really love, but . . . I don’t love dealing with logistics, and pre-production involves a lot of dealing with logistics.

Let me take a step back. I feel incredibly lucky to have gotten a Shift Creative Fund grant. Having the opportunity to make any creative project is a privilege, and getting the resources to do it right is rare. My short film Father Figurine is about a wealthy family forced to lived with the stuffed corpse of their absent father. It takes place at an extravagant mansion. They all wear fancy clothes. One of them rides around on a hover board. And yes, there’s a stuffed corpse.

There are a lot of expensive details, and I never would have been able to make it if I hadn’t gotten the grant. But not every short takes place at a mansion with a stuffed corpse. Some shorts involve tons of VFX or animation. Some involve long, complicated steadicam shots. Some involve just one shot. A lot of really good ones are just one scene. And a lot don’t cost $30,000. But regardless of budget or scope, pre-production is always an exciting and stressful process where you learn a million things (same with production), and prepping the shoot brought up some interesting thoughts.

Working with friends is way more fun. But you need to thank them profusely.

My producer on Father Figurine is Ben Altarescu, who I’ve known for more than ten years, but we became close about four years ago when I asked him if he would produce my short film “Killer.” I don’t know why he said yes, but we spent the next few months prepping and shooting and even more months finishing post. He did all of this for free, and he’s doing it again for this short. Same thing with my cinematographer, Ryan Nethery. That is objectively crazy-town.

Sometimes I don’t know why these people are so generous, but I know that over the course of becoming friends and working with them the past few years, there’s been the feeling of a collective forming, and I know that whenever they have something that they want to make, I’m going to be there for them. And I think that feeling of building a team is really important. Directing is a really selfish thing to do. You’re basically asking other people to make your dreams come true, and even if they’re your friends (or especially if they’re your friends), you need to appreciate everything they’re doing, because you can’t do this alone. It’s way more fun to do it with friends, anyway.

Expanding your creative circle is tough, but it’s necessary and, ultimately, rewarding.

Bringing new people on board a creative project is tough, especially on a short, because you’re asking a lot of people on a small budget. Also, you’re literally emailing strangers. This creates a feeling of desperation that may or may not emanate from your emails. There’s just no way around that feeling, no matter how many times you use the words “passion project.”

This time around, I’ve tried to lean into transparency as much as possible when it comes to talking about what the project involves, and I’ve learned to be more patient when it comes to finding the right person. You just need to trust that you’ve done this before, and if you keep looking, you’ll find your people. As of now, we’ve got an incredible group on board, and the ones that I’ve never worked with are bringing a whole new wave of energy that’s really exciting.

Prepping a shoot remotely has its pros and cons.

We’re shooting this short in the New York area, but I currently live in Los Angeles, so aside from a location scout, I’ve been doing pre-production on the opposite coast. This is the first time I’ve ever done that for a project of this sort, and it definitely has its pros and cons.

The pros are that it’s made me really think about why I wanted to shoot in New York — a combination of creative reasons, as well as the resources we have out there. And thankfully, with this grant, the travel aspect becomes less of an issue.

Also, prepping remotely doesn’t change the work itself that much. There are just more phone calls than in-person meetings, which is actually easier because those are easier to schedule. However, it’s made me feel slightly disconnected from the pre-production process as a whole. I know that might sound nice in theory, but I think it’s way better to be physically there for as much pre-production as possible.

Making a movie is all-consuming, but when you’re not physically there for a major part of it, it doesn’t feel totally real. In a way, I feel like I’m missing out. But, in a few days, I’ll be flying to New York to dive into the final days of pre-production before the shoot, and I’m really looking forward to it.

You have nothing to lose by reaching out to people you think are out of your league.

Between all the projects I’ve worked on, I’ve probably gotten a million rejections — from actors, department heads, locations, film festivals, you name it. Rejection is an unavoidable part of the process, and in a way it’s freeing, because it teaches you that the worst thing that can happen when you reach out to someone is that they’ll say no.

On this project alone, we’ve already gotten plenty of those, but we got one very important yes. As soon as we knew we were making this, we had a specific actress in mind for the lead role, someone who we thought was incredibly talented and would bring a lot to the role, and someone we thought would probably say no.

But we decided to ask (with the help of our casting director, Karlee Fomalont), and to our total and utter surprise, she was interested and is on board! If there’s another nice thing about rejection, it’s that once you get used to it, it makes the moments when people say “yes” that much better.

Remember to have fun.

Admittedly, this is something that I have trouble doing. Sometimes I alternate between thinking that this is the most important thing in the world and telling myself, “It’s just a dumb short.” But I’m still able to remember that this is a creative project, that I’ve been given the opportunity to make something cool with my friends, and that everyone on board is working really hard to make sure that it’s good. I also think that a lot of the stress that comes with pre-production is theoretical, because once you’re actually shooting, everything changes. But I’ll get into that next time.

Oh, also . . . making a stuffed corpse is a fascinating process. I’ll get into that next time, too.

Born just one year after Hammer, three-time Oscar-winning editor Thelma Schoonmaker was honored with a BAFTA Fellowship earlier in 2019. It’s a stunning coronation of a long journey: The Algerian-born Schoonmaker endeared herself to Martin Scorsese at an NYU film study program and helped salvage some botched cutting work on his 1963 title, What’s a Nice Girl Like You Doing in a Place Like This? Nevertheless, Schoonmaker originally struggled to meet the criteria for the editors union in the 1970s, and her career stalled as a result. Her first Oscar nomination came in 1971 for Woodstock; her three wins were for Raging Bull, The Aviator, and The Departed. Schoonmaker works with Scorsese to this day and is listed as the editor of his forthcoming film, The Irishman. “I think the women have a particular ability to work with strong directors,” she once said. “They can collaborate. Maybe there’s less of an ego battle.”

Born just one year after Hammer, three-time Oscar-winning editor Thelma Schoonmaker was honored with a BAFTA Fellowship earlier in 2019. It’s a stunning coronation of a long journey: The Algerian-born Schoonmaker endeared herself to Martin Scorsese at an NYU film study program and helped salvage some botched cutting work on his 1963 title, What’s a Nice Girl Like You Doing in a Place Like This? Nevertheless, Schoonmaker originally struggled to meet the criteria for the editors union in the 1970s, and her career stalled as a result. Her first Oscar nomination came in 1971 for Woodstock; her three wins were for Raging Bull, The Aviator, and The Departed. Schoonmaker works with Scorsese to this day and is listed as the editor of his forthcoming film, The Irishman. “I think the women have a particular ability to work with strong directors,” she once said. “They can collaborate. Maybe there’s less of an ego battle.”