“Point and shoot” has become commonplace in today’s world. Pull the phone out of your pocket and start recording. Many NLEs have embraced this trend by allowing creatives to begin editing their camera media instantly, as opposed to older workflows that involve transcoding (converting) the original media into a more edit-friendly codec (format).

This instant gratification factor is very attractive to creatives but also has the unfortunate potential downside of technical problems later in post-production. This is where we encounter a well-known truth in post-production.

Pay now or pay later

In short, pay now means taking the time to shoot content in a format that is friendly to post-production tools, or at the very least, prepare non-edit friendly formats into friendly ones.

Pay later, on the other hand, affords you the ability to edit the camera originals instantly while pushing technical hiccups to later in the post-production process, where format problems can snowball quickly.

In virtually every post-production scenario, planning to pay now is infinitely better than pay later. Why? Another post-production truth: you have more stress and time constraints approaching your deadline than you do when post-production starts.

“There is never enough money to do it right, but there is always enough money to do it again.”

So, what can you do to ensure that we pay now and prepare our production and post-production for success? Shoot in edit-friendly codecs.

These include:

These formats are easier to edit because each frame recorded by the camera contains the complete set of data to display that frame. Often, you can begin editing immediately after recording.

Other formats, such as:

…are easy for cameras to shoot but are often very difficult to play back in video editors. Why? These formats are known as Long GOP (long group of pictures), which do not contain enough data in each frame to display that frame on its own. The NLE needs to look at many adjacent frames to determine what the single frame looks like. This puts strain on your computer and software and can make playback – let alone real-time visual effects – difficult, if not impossible.

However, if we transcode (convert) these Long GOP formats into the aforementioned edit-friendly codecs such as ProRes, DNxHR or CineForm, your NLE will play back, scrub faster and handle more real-time plugins and filters. To be clear, this won’t improve the quality of your footage, but it will make that footage easier to manipulate in post-production.

Now, if you have the option to shoot in a (true) RAW format, do it. RAW formats were designed to capture even more information in a single frame than the edit-friendly codecs listed above. You might have guessed – this forces you to pay now; as these RAW formats expect that you will transcode those camera original files into new files to work with in post-production – and then potentially relink to the RAW originals later in the post process.

Now what?

An often neglected step is to test your workflow before you shoot. You’d think this would be a no-brainer, but often the assumption is that whatever is shot on location will just be handled by post-production. This fatal flaw can often cause chaos in post-production, which then reduces the time post-production creatives can work on your project. Make your project memorable by letting creatives create for as long as they can and spending less time fire-fighting issues with camera formats from on set.

Save yourself the stress. Ensure post-production has media in formats that are easier to edit, and test your workflow in its entirety to reduce the chance of technical problems.

Want tips on navigating the approval process? Download our guide to Making Memorable Television.

MediaSilo allows for easy management of your media files, seamless collaboration for critical feedback and out of the box synchronization with your timeline for efficient changes. See how MediaSilo is powering modern post production workflows with a 14-day free trial.

As you sit and stress about all the different people who have to give an episode of your show their blessing, it can seem like there are way too many cooks in the kitchen or that the approval process is byzantine and endless. But all time and layers of the approval process are there for a reason, and you can use them to create a better show. It’s all about understanding why each stage is there and what it’s supposed to accomplish. Think of those layers as chances to make the show better rather than hurdles to clear. Your team was assembled because of its experience, creativity and skill. The approval pipeline can be the key to unlocking all of those assets.

The Order of Operations Exists For a Reason

While the showrunner’s approval is often the primary goal, and the most important consideration, the approval process in episodic television also involves a number of other stakeholders, and there is a traditional order to the creation process for a reason.

Initial assembly

Once filming for a given day has been completed, the footage is sent to the editor. In most cases, editing work is anywhere from one to three days behind the actual filming, up until the episode’s shoot schedule is complete. The editor may be working remotely or may actually be on set, which can help close the gaps between what is shot and what is needed in the episode. In that time, the editor will usually make a first assembly, trying to get all the basics of the story and structure into a working cut. The editor will typically have between one and six days after receiving all the dailies to create an initial assembly to send to the director. That stage is very important structurally and adds a lot of value to the final episode, because editors tend to work on multiple episodes and are usually more familiar with previous episodes and the show’s ongoing tropes and style.

As the footage is given to the editor, the director will usually provide some direction about how the episode should be put together. At the same time, the script supervisor has usually provided notes and insights based on what happened on set. These notes also add value and often can help the editor discover aspects of the footage that might not otherwise have been apparent.

The director’s cut

Once the episode’s filming is complete, the director and editor will work for up to four days to make the director’s cut of the episode, which is normally the first official milestone in the post-production pipeline. Before the pandemic, it was common for directors to physically sit with the editor while working on the director’s cut if the director wasn’t committed to working on other projects immediately. That opportunity for close collaboration was a valuable part of the process, and trying to maintain that same level of interaction with today’s workflows is an important consideration. With modern production tools and workflows, live remote editing can accomplish many of the same things, and the rest is achieved through digital collaboration platforms such as MediaSilo, email and any other means available.

While creating the Director’s Cut, the director and editor can drill down on specific shots to ensure delivery of the showrunner’s vision.

Episodic television is an unusually collaborative medium, and great shows benefit from the creative imprints and inputs of every team member. Even though there will be other levels of approval after the director’s cut, it’s important to treat each one as a separate stage, because each one adds a different value to the process. Skipping ahead before creating the best director’s cut can leave great creative ideas on the editing room floor. Many of the industry’s top showrunners like to let the director experiment a little at this stage rather than insisting on having them present the script as shot. Making sure the director at least gets to the point where the cut lines up with the vision of what they were trying to shoot is a critical part of creating the best final product. This is even more true in serialized shows, which are often less dependent on a strict formula.

Because directors tend to only work on just one episode per season (or a small handful), a talented helmer often can provide new ideas and insights that might have eluded the ongoing team members. Focusing on the ideas of the director at this point helps introduce fresh and exciting ideas that haven’t been part of other episodes. There will be plenty of time to get things back in line with existing stylistic aspects of the show afterward, but the director’s cut provides a unique opportunity to get original input into the episode from a new viewpoint. And this kind of input can help keep a show interesting to viewers, eliminating predictability and repetition.

The showrunner steps in

Once the director’s cut is complete, it’s time for the showrunner and producers to come into the process and make the episode part of the greater whole. As the central creative visionary behind the show, the showrunner needs to make sure that the cut fits with the previous episodes and that it leads properly into planned upcoming episodes that haven’t yet been filmed. While the director may have treated the individual episode as a standalone creative opportunity in some respects, it is the showrunner who makes sure that the episode fits with the entire show’s arc. Just as the director’s cut provides new ideas, the showrunner makes sure those ideas fit with the overall direction of the series.

This stage is also when the showrunner may get input from the writers and other producers to ensure that the episode is coming together as they had envisioned. The showrunner collects notes from the team and makes sure the cut is working for them before finalizing the producers’ cut. Because the showrunner is the show’s creative shepherd, this stage of approval is the most critical creative stage for the episode’s outcome. If the showrunner is happy, then chances are most others will be as well.

Other stakeholders make their mark

While the showrunner represents the show’s creative vision, episodic television is a business, and there are many concerns and interests involved. In some cases, the showrunner’s cut will move forward in the post-production pipeline with only minimal additional input from the studio, network, and sponsors. But those viewpoints are still very important aspects of the creation process. Once the showrunner is satisfied with the episode’s rough cut, it’s time for the producing studio’s producers to weigh in. Just as the showrunner is focused on maintaining the creative vision and protecting the story, producers will have the studio’s interests in mind. They might be thinking beyond the story or individual show to how it reflects on their larger plans. Beyond the producing studio, there are also network stakeholders and executive producers who need to weigh in on how the episode fits with the image of the network and with the needs of potential advertisers or sponsors. And in some cases, those advertisers or sponsors may even get to review the content themselves.

Though some may think of this part of the process in purely negative terms, it also can present an opportunity, creatively speaking. The best producers will use this stage as a chance to make the show even better, not just rein it in and keep things “safe.” Any creative person can sometimes get too mired in personal aspects of a story or be too close to it to see flaws. A savvy and experienced producer, while also seeking to represent the studio, network or stakeholder’s interest, might also be able to provide insight into the minds of the larger audience and what is likely to appeal to them. So this stage, when used correctly, can actually improve the final product by making it more universal and helping connect the show more deeply to the audience.

Using each of these approvals as a way to make the show better is the way to end up with the best product at picture lock. It’s important for the creative team to be open enough to outside input that opportunities aren’t missed. At the same time, it is incumbent upon the studio, network, and sponsors to operate from a place of creativity and opportunity rather than fear and defensiveness. Make things the best you can rather than the least risky. No one remembers safe, and that’s usually more dangerous than any risk you might take.

The finishing touches

While the showrunner has been the guiding figure through edit approval and picture lock, there’s still work to be done. Generally speaking, the picture-locked cut will still require a whole range of adjustments, including the creation and insertion of visual effects, sound design, additional dialogue recording, and color correction. And many of these elements will be created by outside vendors and post houses. With the showrunner less present, it usually falls to the Post-Production Supervisor or Post Producer to bring it all together and make sure all of these elements proceed in a way that enhances the final product. In a perfect world, each of these elements has a chance to make the show better and more engaging. And while the showrunner and producers will eventually sign off on the finished product, it’s the Post-Production Supervisor or Post Producer who must make sure it’s all going according to plan.

Once all of the finished elements are in place, the editor or editors will be asked to check all of the post-work and make any needed adjustments. The mix will be reviewed on a mix stage or at the post house. Then the showrunner and writers will give their signoff and sometimes be part of the team that attends the final laybacks. If all goes well, there are few surprises or changes at this point because communication has been consistent and thorough.

In the next installment of our guide, we will look at how each player on the production and post-production teams can put their mark on a show and make it better than the sum of its parts.

Part 2 Recap:

- Each approval stage serves a specific purpose, as does the order in which the stages are arranged.

- The editor provides much-needed continuity between episodes and can be a great resource on what stylistic choices have already been made.

- The editor can be the primary conduit between the script supervisor on set and the actual content of the show. This helps keep things from slipping through the cracks that could be costly later.

- The director’s cut can provide fresh ideas and useful insights from a new perspective. Even though the showrunner will have final say, focusing on the director’s cut first allows the director to demonstrate what they had in mind when shooting. It can also provide a perspective from a skilled voice that isn’t so close to the show and applies to the specific episode. This helps keep the show fresh and interesting for viewers.

- The showrunner must be sure to keep the big picture and overall themes consistent. They’re the link between all the talented team members and the original vision.

- There are a wide variety of interests and business motivations beyond the story itself. This can be used as an advantage, not just a hassle.

- The network and producers often have special audience (and sponsor) insights.

- It’s always dangerous to be “safe.”

- The little details added at the end can often elevate the entire show.

Read the entire 3-part guide to Making Memorable Television now.

For other tips on post-production, check out MediaSilo’s guide to Post Production Workflows.

MediaSilo allows for easy management of your media files, seamless collaboration for critical feedback and out of the box synchronization with your timeline for efficient changes. See how MediaSilo is powering modern post production workflows with a 14-day free trial.

The problem of poor playback performance is a serious issue for film and video editors.

Regardless of whether you’re editing in Avid Media Composer, Adobe Premiere Pro or Apple’s Final Cut Pro, or even color grading and finishing in Blackmagic Design’s DaVinci Resolve, every system can experience poor playback at one time or another.

The entire creative process comes to a shuddering halt when you can’t get your system to show you every frame of footage as it should. When you get dropped frames, jittery or sluggish playback or encounter a system that is lagging behind your commands, it’s nearly impossible to get anything done. Speed, fluidity and instantaneous execution of commands are all essential to fast, efficient film and video editing.

But the reason for poor playback performance can originate in a number of different places:

- Is your computer just not good enough to play back the high-resolution footage you have?

- Is your hard drive too slow to throw the data onto your timeline quickly enough?

- Is the connection port or cable the real bottleneck in your workflow?

- Is your codec too tricky to decode?

In this concise guide to troubleshooting poor playback performance, we’ll take a look at all of these issues in turn.

If you’re working on large, network-connected tiered storage systems, you’ll need to consider things like network speeds, file management, user management, load balancing, etc., which are outside the scope of this guide.

That said, the general principles we’ll discuss are still very relevant to getting things to work as they should. But the key focus of this guide is for editors working on direct attached solid-state drives (SSD), RAID arrays or big spinning hard disk drives (HDD).

Troubleshoot Your System by Understanding Your Footage

The first step to troubleshooting your poor playback is to analyze the qualities of the footage you’re trying to work with. This will provide you with some essential information to help you benchmark your system against and narrow down where the problem might be.

Footage Analysis

Find out the following pieces of information about the footage you’re trying to work with, as they all have an impact on the process:

- Frame rate

- Frame size/resolution

- Codec

You’ll then need to look up the data rate of the footage given these parameters.

For example, let’s say you’re working with 4K ProRes 422 HQ from an Alexa 35 at 24p.

The data rate for that is 799 Mb/s (megabits/second) according to ARRI, as the clip resolution is slightly larger (4096 x 2304) than the 754 Mb/s listed in the Apple ProRes White paper from Apple for 4096 x 2160.

Most hard drive performance numbers are given in megabytes (MB/s) a second, while these figures are in megabits per second (Mb/s). As there are 8 bits to a byte, you just need to divide the data rate number by 8.

799 Mb/s divided by 8 = 99.8 MB/s for one stream of our 4K ProRes 422 HQ at 24p footage.

A four-angle multicam edit would therefore need at least 400 MB/s of throughput performance from the source drive and the cable connecting it to the system.

Understanding Hard Drive Speed

Different types of media storage can operate at different speeds. In today’s edit suite, most of us are working from a range of solid-state drives (SSD), hard disk drives (HDD) with spinning disks (5400rpm or 7200rpm) or RAID arrays which deliver speed and redundancy benefits by enabling several individual disk drives to act as one big fast drive.

Here are some ballpark read speeds for these common types of drives:

SSD

- USB 3.2 SSD = 1050 MB/s

- Thunderbolt 3 NVME SSD = 2800 MB/s

HDD

- 7200rpm Thunderbolt 3 drive = 260 MB/s

- USB 3.0 5400rpm drive = 200 MB/s

- Local RAID with 7200rpm drives = 567+ MB/s

So now that you know the data rate of the kind of footage that you’re trying to pull from your media storage and the typical read speed of your storage, if the data rate demands of the footage exceed your storage performance, this could be the root cause of your playback issues.

In our example of the 99.8 MB/s data rate for a single stream of 4K ProRes 422 HQ at 24p, we should be fine editing from most of these drives relatively easily.

There’s a lot more we could say about each of these media storage types, but one general principle that applies to them all is that performance tends to decline as the drive gets full. As a rough rule of thumb, you want to try to keep to about 80% of the maximum capacity before you start to see a degradation in performance.

Understanding Port and Cable Bandwidth

One other consideration that is intimately connected with hard drive speed is that of the port and cable type that is connecting the drive to your system. Sometimes the cable is labeled with its specification but not always, and unfortunately, you can’t make assumptions about the speed based on the shape of the connector alone.

If you are connecting a fast drive over a slow port and cable, then you obviously won’t reap the benefits of all that source-side performance.

Here are the typical (advertised) speeds for several common connections:

- USB 3.0/3.1 (Gen 1) with USB Type-A connector = 625 MB/s

- USB 3.1 (Gen 2) with USB Type-C connector = 1250 MB/s

- USB 3.2 with USB Type-C connector = 2500 MB/s

- Thunderbolt 2 = 2500 MB/s

- Thunderbolt 3 with Type-C connector = 5000 MB/s

Note – Bandwidth speeds are often listed in Gbps (Gigabits per second) where 1 Gbps = 125 MB/s. I’ve done the conversions above to keep all of our numbers in MB/s.

So, again, if the combined data rate of every video stream you’re trying to access at the same time on your drive exceeds the throughput performance of the port and cable you’re pulling it through, then this could again cause playback issues.

It’s also worth noting that these ‘advertised’ speeds are usually the ‘theoretical’ maximum performance of the connection, while real-world numbers are likely to be south of these.

When purchasing a new USB 3.X drive, it’s also worth double-checking exactly which type and generation it is, as this will dramatically affect your potential maximum speeds.

Understanding Basic System Performance

Finally, it is also worth considering the capabilities of your system when it comes to handling the kinds of footage you’re using in your project, in conjunction with any computationally intensive effects, filters and transformations you might be applying to it.

Returning to our initial footage analysis, the frame size, frame rate and codec type all combine to determine how difficult they are for the system to display.

The first two parts of this are fairly intuitive. If you have a bigger frame size, such as 4K over HD, or more frames to display from a higher frame rate, such as 60 fps vs. 24 fps, this will require more system resources to work with.

But in many ways, the codec type plays a more influential role in determining your playback performance. The word codec stands for compression/decompression, and each codec uses different mathematical calculations to initially compress the information from the sensor into the file and then decompress it to view it.

Different codecs are designed for different things. H.264 is great for creating small files that can be displayed on the web, but it’s not great for editing from. Conversely, something like ProRes is designed specifically for modern editing workflows and is ‘easy’ for a system to handle, but consequently has much larger file sizes.

There’s a lot more that could be said about the role of codecs in video editing, but we’ll leave that for another time.

If you’re also adding a lot of effects, color grades, third-party plugins or other render-intensive adjustments such as temporal noise reduction, then these will also tax your system’s capabilities.

Depending on (and the version of) your video editing software of choice, it may or may not be optimized to work best with the hardware you’re running it on. For example, newer Macs that are running Apple Silicon chips (M1, M2, etc.) are very fast, but only if the software has been rewritten to make use of the way the chips like to do things

It’s also worth noting that internal settings in your video editing software, such as ‘enable high-quality playback’ in Adobe Premiere Pro, can have a dramatic impact on the quality of interaction you have with your footage. These are also worth investigating.

Putting it All Together – Testing Your System

So now that you understand the characteristics of the footage you’re working with and its specific data rate, the speed of your media storage and the bandwidth of your connection, you should have all of the information you need to understand if what you’re trying to do is a viable workflow.

One excellent tool for testing your system performance is the free Blackmagic Design Speed Test app, which writes and reads some test data to your drive and delivers a performance report.

It also helpfully tabulates which common video codecs, frame rates and resolutions will work on your system.

The results in the image above are from my MacBook Pro’s internal hard drive.

If All Else Fails – Create Proxies

If all else fails and you still can’t get decent playback, then it might be worth creating proxies instead.

This is the process of converting your footage into a more manageable codec and file format for your system. Proxy files are often used when the source footage is very high quality, such as 8K RAW files, which are both resource intensive and take up a lot of hard drive space.

By making smaller, lower-quality proxy files that feature smaller bit rates and easier-to-handle codecs, all of the creative decisions can still be made while working with these, and then the final edit can be relinked to the original full-quality media at the end for final color grading and delivery.

Although working with proxies does add a further layer to your workflow, most video editing software these days will automatically manage the proxy process for you by both creating and toggling between the full-quality and proxy files with just a few clicks.

Save Time With the Playback Performance Cheat Sheet

Download this cheat sheet of the speed requirements for common codecs and a bunch of standard drive speeds and port speeds to quickly identify the crucial data to troubleshoot poor playback performance on your system.

For other tips on post-production, check out MediaSilo’s guide to Post Production Workflows.

MediaSilo allows for easy management of your media files, seamless collaboration for critical feedback and out of the box synchronization with your timeline for efficient changes. See how MediaSilo is powering modern post production workflows with a 14-day free trial.

What Kind of Show Are You Making?

It’s 9 pm on a Friday night, and you’re sitting in the edit suite waiting for the notes to come in on your fourth version of the rough cut. As you wait for all the stakeholders to weigh in, you think about what a normal person would be doing right now, and you wonder what you could have done to make this whole process go as smoothly and perfectly as possible.

Whether you’re making a gritty documentary-style OTT streamer, a strictly structured long-running network procedural, or a slick and inventive serialized narrative for a subscription cable outlet, there are certain things you should be thinking about to help you create the best episode you can make with the least stress and heartache.

We spoke with veteran editors, post supervisors, episodic directors, and showrunners about what matters most to them and how they get so much done in so little time. While there are huge variations between show types, there were definitely some universal truths that emerged, and we believe these are the key to a successful episodic television pipeline.

Is it a cut-up feature film, or is it a series of short films?

Episodic television production is unique in that it combines some aspects of feature film production with some aspects of making shorter pieces. In a sense, an episodic television season can be looked at as a series of individual 22-minute to 60-minute short films about a single topic. But it can also be seen as one epic 8-16 hour feature film that has been cut into installments. And in recent years, some of the lines between feature production and episodic production have become even more blurred. Ultimately, the nature of the show you’re making can determine which of those is the best framing for your project.

When you’re working with a classic procedural format like the various Law & Order properties, you become very familiar with your existing formula and characters. However, each episode stands on its own as a story. So when working on that type of procedural, it’s probably useful to think of each episode as a short- or medium-length film with its own arc, even though you will be keeping track of certain throughlines and ongoing aspects. Meanwhile, if your show is a serialized drama like The Handmaid’s Tale or Better Call Saul, you’re usually going to be treating an entire 10-13 episode season more like a single, very long feature film, with a plot arc that unfolds over the course of the whole season. This aspect is what makes it binge-worthy. So the approval process may involve some different considerations as the structures and goals are different.

Comedies are similar, with many sitcoms essentially following procedural episodic guidelines, without requiring that your viewers watch them in order. In a thematic sense, and in terms of the practical aspects of putting together your episodes, each installment stands alone and you can approach them on a more individual basis.

Meanwhile, if you’re working on a comedy with ongoing plot lines that require having viewed previous episodes to varying extents, you’ll be using aspects of the “season as a film” approach as you put your show together. Arrested Development is a good example of the latter type of show and surely had different structural and approval considerations from traditional sitcoms. There are also shows that fall somewhere in between, where things that have happened in earlier episodes are acknowledged or referenced in some way, but may not be as critical to constructing later episodes.

Documentary series, while totally different in content, can also follow either of those formats depending on the structure of the show. So if you’re working on a competition show like The Bachelor or Survivor you’re likely to be following an approval and review pattern similar to serialized dramas and need to keep in mind the whole season’s arc as you build the episodes. Meanwhile, many game shows and travel shows don’t require having viewed previous episodes, so your approval process will have more in common with documentary shorts and films. Regardless of format, we have tips and procedures that can help you guide your program smoothly from shoot through final post-production.

Maintaining the show’s creative vision

The most important aspect of guiding an episode of television through to final approval is making sure the episode maintains the show’s overall creative vision. Is the episode you’ve made consistent with the others? And does it fit in well with the overall arc of the show? If it’s a serial format, does it feel like a continuation of the story as it was left in the prior episode? It should move the story forward, but also connect seamlessly with what has come before. If you think of the latest episode as the latest part of an ongoing feature film, it should work in that context, not just on its own.

If it’s non-serialized, then does the episode feel similar enough to other episodes that it clearly shares the same DNA? Each episode should add something new and fresh but still provide the same types of satisfaction and enjoyment, as well as the same structural elements as previous episodes.

Whether narrative or documentary, the final word creatively usually comes from the person designated as the showrunner. It is the showrunner who will guide the overall direction of the series. While feature films are most often led creatively by the director, episodic television usually requires multiple directors to meet a show’s production schedule, and the showrunner fills the creative leadership role that would typically fall on the director in a feature film. There may be many other stakeholders on a large-scale production, and each episode has different directorial leadership, but the showrunner is the most significant in terms of getting the final work approved and in maintaining a unified creative vision despite having different team members on each episode.

Whether you’re editing, leading post-production, creating visual effects, or mixing the audio on an episode of television, the most important aspect of your work will be making the episode fit in with the overall thematic vision that the showrunner has for the series. And if the showrunner is happy with the product, chances are it will eventually get approved for air.

Know your showrunner, know your show

Like every creative person, you have great ideas. That’s probably why you got into the creative world in the first place. But great ideas aren’t always the right idea. Anyone who has ever experienced the pain of “approval by committee” knows the importance of having a focused creative vision and a limited number of people in charge of it. It’s the only way to tell a cohesive and compelling story. That’s why episodic television assigns a showrunner in the first place. And while everyone’s great ideas have the potential to be part of making a show great, it’s also important to know the showrunner and the show itself very well.

The best thing you can do to make your creative contributions valuable is to make them consistent with the vision and existing intellectual property of the series. That’s not to say there isn’t room for creativity, but a patchwork quilt of styles and processes doesn’t help when trying to create a unified piece of entertainment. So the better you know the creative vision of the show overall, and the better you know the established elements, the more likely your contribution is to be helpful.

The importance of overlaps

The television production process can seem hopelessly compartmentalized when not executed correctly. Communication between production and post production can feel very minimal at times, and creative stakeholders aren’t always present at critical stages of post production. Every separation creates the risk of a communication breakdown or misunderstanding.

The way to make sure that a unified creative vision is maintained throughout the process is to create overlaps in understanding. If the editor is walking into the first assembly essentially blind and is learning the story elements for the first time, the chances of having a great first cut go down fast. Before the show even starts, the first thing everyone involved on the team can use to get on the same page is the show bible. The show bible will help bridge the gap between all departments and ensure everyone is aligned on the same vision. So it’s important for everyone to be familiar with it.

But there are also tools that can help different departments and stages of the creation chain connect more seamlessly on an ongoing basis. For example, if the editor attends the tone meetings that happen before each production block, where the showrunner and director talk about the story beats, the editor can gain priceless insights. Similarly, if the colorist is working in a vacuum to make the show look as good as possible, the episode may or may not reach its potential. But if the Director of Photography gets to sit with the colorist and they get to work on the grade together, great things can happen. Finding connections that turn the potential telephone game into a smooth transfer of information will make the difference between making a cohesive show and flailing blindly. Don’t give up any opportunity to connect team members from various departments.

In the next installment of our guide, we will look at the approval pipeline and what each stage is trying to achieve so that you can optimize each part of the process.

Part 1 Recap:

- Figure out whether your season makes more sense as a series of separate short films or as one long feature that has been broken up into installments. Each has its benefits, but one will always be a better fit for your show.

- Regardless of whether it’s documentary or scripted, comedic or dramatic, a show’s structure will determine which approach you take.

- Figure out whether you need to prioritize the season’s overall throughlines or each episode’s individual structure first.

- Always try to match existing canonical elements of style and tone. When in doubt, step back and think about how the current episode fits in with all those that came before (and those still to come).

- Try to give the audience what they loved about past episodes, but with new twists to keep it from feeling expected.

- There are many stakeholders with sometimes conflicting goals. But the showrunner’s vision is the glue of the show. When in doubt, try to make the show that the showrunner envisioned and let the showrunner defend it to other stakeholders.

- Try to create overlaps between departments and stages to keep everyone on the same page. Invite team members who will work on later stages of the episode to attend meetings and sessions earlier in the process so your visions are aligned. (e.g. The editor can learn a lot by being present for story meetings. And the colorist gains valuable insights from the DP.)

- The more information you give each team member and department, the more useful their contributions will be. Facilitate connections between departments that might not otherwise get to communicate.

- When in doubt, use the show bible as a reference to keep everyone on the same page throughout the process.

Read the entire 3-part guide to Making Memorable Television now.

MediaSilo allows for easy management of your media files, seamless collaboration for critical feedback and out of the box synchronization with your timeline for efficient changes. See how MediaSilo is powering modern post production workflows with a 14-day free trial.

When it comes to making a standout product video, finding the right team and the right workflow is key. At MediaSilo, we worked with a number of production teams before we found our fit with Vidico, a full-service production company based out of Melbourne, Australia, specializing in brand and product videos for technology companies. Over the course of several successful video projects together, we developed a plan that worked seamlessly at each stage of the creative process.

The pre-production phase can be the most crucial stage of the entire video creation process to ensure a quality final product that matches your vision and brand.

This year, the MediaSilo and Vidico teams came together to produce the launch video for our latest feature Spotlight, a fully customizable site-builder within MediaSilo, to present and showcase your work with branded microsites and presentations. Project leads Tim, Producer at Vidico, and myself, Product Marketing Manager at MediaSilo, put our heads together to share these four best practices for producing successful product videos.

1. Prioritize the pre-production phase

The pre-production phase can be the most crucial stage of the entire video creation process to ensure a quality final product that matches your vision and brand. This is the stage where you gather the team for brainstorming, and hash out any creative differences. From a cost standpoint, it’s much easier to change a sketch or PNG file than it is to change an entire animation.

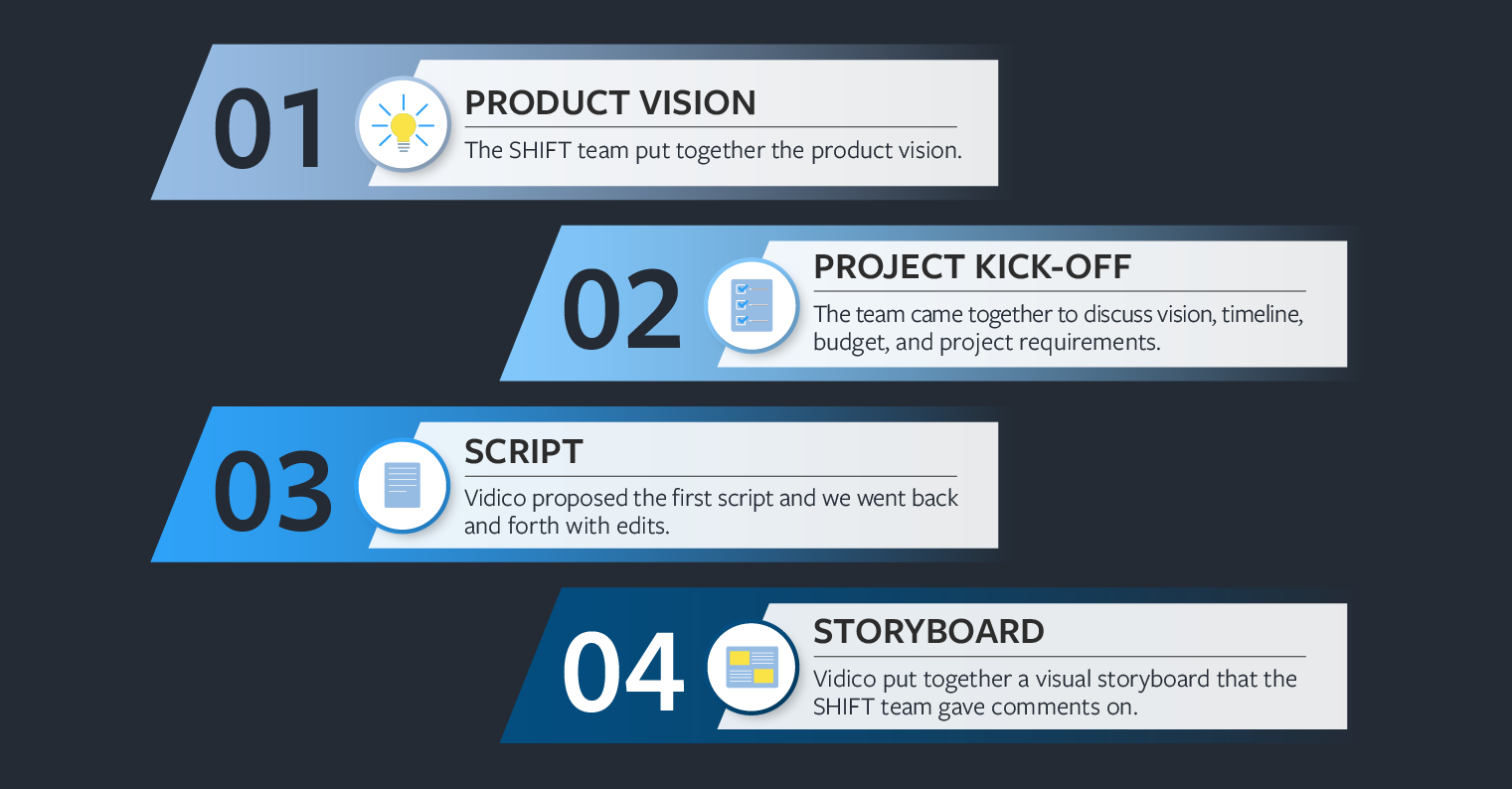

Our pre-production phase looked like this:

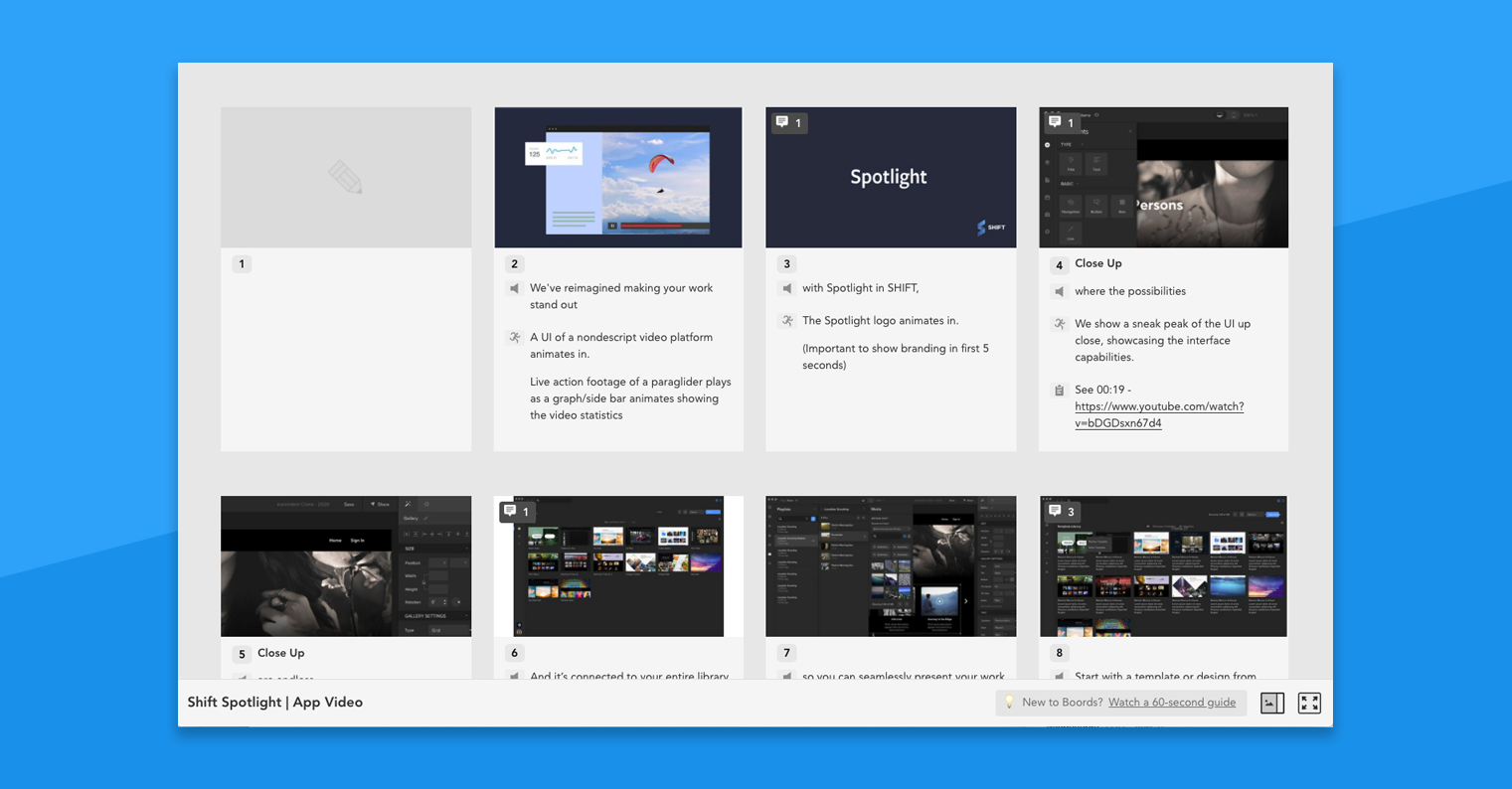

The script and storyboard phases are where the marketing team will want to really hone the details. We used Dropbox Paper to collaborate on the script, where we documented important project information and made use of commenting features to communicate asynchronously. Then, the Vidico team translated the written script into a visual storyboard using Boords, where the MediaSilo team was able to comment directly on individual slides.

With Boords, the MediaSilo team was able to make notes on individual storyboard slides.

When MediaSilo brought their product expertise and brand vision to the table in a clear and concise way, Vidico was easily able to propose creative to fit the bill. Once the storyboard is finalized and off to production, it’s mostly up to the animation team to bring the story to life.

2. Identify your stakeholders for each stage of the project

For a big launch like this, teams across the company will need to be aligned to balance the number of cooks in the kitchen. Not everyone needs to have a say on the color of the text or minor design details, but all key stakeholders should be looped in to provide input on the overall direction and messaging of the script and visuals.

Your stakeholders should include leaders from Product, Sales and Success teams who can help identify key “marketing features” that will hook prospects in.

Your stakeholders should include leaders from Product, who can help outline the overall direction of product messaging, and leaders from Sales and Success teams who can help identify key “marketing features” that will hook prospects in. Early on, the MediaSilo team identified its product stakeholders as our VP of Product and CEO, and its go-to-market stakeholders as the VP of Sales and Director of Enterprise Success.

We checked in with our internal stakeholders at each stage — briefing, scripting, and storyboarding — and made sure to over-communicate to avoid delays.

3. Establish project leads on each team

We created a shared Slack channel for the MediaSilo and Vidico teams to stay in touch on a daily basis.

Tim and I divvied up responsibilities at the beginning of their project to make sure both teams were on the same page.

- Jane (Product Marketing) was responsible for developing the project vision from the MediaSilo team, organizing and facilitating project meetings, gathering timely feedback from stakeholders, and establishing feedback protocols at each stage of the project.

- Tim (Producer) was responsible for keeping the project on time and budget, ensuring timely delivery at each stage of the project, as well as managing the creative and animation team at Vidico.

Since our teams were working across a 16-hour time difference (!), it was important to find a way to communicate quickly and efficiently. To solve this, MediaSilo and Vidico created a shared company Slack channel that we could all access from our own MediaSilo and Vidico workspaces. We took advantage of threads for sidebar conversations about details, and Jane and Tim made sure to broadcast channel-wide messages for record-keeping or when hopping on a call wasn’t possible.

4. Keep all your files and feedback in one place

There’s nothing quite as satisfying as using our own app to wrap a project. We created a dedicated project in MediaSilo that all project members had access to, and a subfolder for the Spotlight video.

We leveraged the time-coded review features in MediaSilo to make drawings and comments right on the video and track changes across versions.

The Vidico team would animate the project into life using Adobe After Effects (which MediaSilo now integrates with) and Tim would share the latest cuts as a secure link for the MediaSilo team to comment on in a 2-day turnaround window. We went through a few review cycles, first on the overall flow, music, animation edits, and finally some color and design tweaks.

Vidico’s animation team worked in Adobe After Effects, which MediaSilo now integrates directly with.

The Finished Product

With the right team, workflows, and tools, putting together a product video can truly level up your product launch, attracting the prospects you want and enabling your Sales and Success teams to do their jobs.

Get started with a trial of MediaSilo today to streamline your team’s video collaboration. And, if you’re looking for more best practices like these, subscribe to our blog and we’ll send them straight to your inbox.

The rules have changed when it comes to how products and services are sold on television and online. Branded content has brought about a shift in commercial advertising, with creatives finding new ways to craft and tell stories no longer limited to 30-second or 60-second spots. Matt McDonald (BBDO), Trevor Guthrie (Giant Spoon), filmmaker and honto88 founder Shruti Ganguly, Ben Hughes (Squarespace), Angela Matusik (HP), and Ad Age associate creativity editor I-Hsien Sherwood gathered at IFP Week earlier this fall for a panel titled “Don’t Call It A Commercial” to discuss how the line between entertainment and advertising has blurred.

They addressed finding and knowing your audience, striking a balance between art and work, daring to buck convention, and knowing when to walk away. We pulled four insights from their discussion to illustrate the power of branded content for effective storytelling, as well as for selling products and ideas.

Going beyond 30- and 60-second spots

The status quo works until it doesn’t. Discussing commercials as vehicles for delivering messages, Ben Hughes, director of the brand creative team at Squarespace, suggested that as time passes, adaptation and innovation become necessary. “It’s really important to remember that there’s nothing sacred about a thirty or a sixty,” he said, referring to the traditional lengths of television commercials. Those blocks of time were sold by broadcasters to advertisers, who in turn had to find ways to tell stories confined by those time constraints.

Today that model isn’t the only one that holds.

While the 30-second commercial works for “snappy” ads, Hughes believes storytellers occasionally need a longer, wider, and more dynamic runway. “Anywhere where you need to get under the surface of something, explain something more complex, or want someone to have an experience with something that is closer to an experience you have with art,” he said, “longer form can make a difference.”

The medium is the message

Contemporary advertising media is more expansive than it was in the 1940s, when the first commercial aired on television. There are still magazines and billboards, but brands can now use podcasts, social media, digital platforms, and experiential activations at festivals and conventions to tell a story. Branded content creators must determine which of those channels best fits the audience they want to reach. “We’re taking our stories that aren’t really even about products or brand, but about a feeling or emotion or an idea that is part of our DNA and pushing them out on platforms where we know people are,” said Matusik.

“We’re taking our stories that aren’t really even about products or brand, but about a feeling or emotion or an idea”

“The thing that we’re doing is trying to build these worlds and then transport people into them,” Guthrie said about the immersive fan experiences that his company designed for Game of Thrones, Blade Runner 2049, Westworld, and other media properties. At the core of it all is the story; experiential marketing is just a different way to get from the beginning to the middle and the end, he continued.

The medium is in service of the goal. For McDonald, the Faces of Distracted Driving campaign he worked on for AT&T sought to get people to put down their phones; as a format, 30-second commercials weren’t good enough. Instead, BBDO created a series of videos featuring interviews with families affected by distracted driving.

“Can watching the story of this family and seeing the trauma and hearing them talk about just how they’re struggling with their lives ten years later and really exploring that over the course of seven or eight minutes — does that convince you to put down your phone?” he asked. “For me and for a lot of other people, it did.”

Sell-outs no more

There are artistic components to advertising and branded content, but the end goal is always to sell, be it an idea, brand, or product. How do creatives reconcile the idea that they’re just another cog in the corporate wheel and that their vision has been compromised? Matusik believes that, while many artists, filmmakers, and storytellers used to feel like their voices were being “muddled” or that they were sell-outs for working with brands, their attitudes are changing.

“As a roomful of filmmakers, you should be thinking about ways that you can speak true to your voice and what it is you’re trying to accomplish,” she told the audience. “Think of a brand as a partner. If you can find the right one that has a similar alignment or goals in mind, that’s how you create great work.”

Taking care of biz

Speaking for creatives, Ganguly emphasized the business side of brand partnerships, which come with added responsibilities. “You have a client that has an audience and a purpose and a reason for spending that money. That short or project that you’re working on with them has to fulfill a bigger purpose, and you have to stick to your deadlines, stay within budget, and deliver,” she said. “The guidelines have to be set forth, and they have to be followed, and there are no excuses.”

Collaborative partnerships, not compromised relationships

Having worked with Hollywood directors including Kathryn Bigelow and Taika Waititi, McDonald finds that the best ones understand that making anything is a process. Collaborating while also being able to articulate and defend one’s vision is key. “It’s not necessarily like you’re losing if your vision is compromised,” he said, adding that it helps to take notes when given feedback and to find a different path to quality content.

In the end, it’s also important to recognize when a partnership with a brand isn’t going to work and to have the courage to walk away.

Size queens, beware: When longer isn’t better

While branded content has largely broken the mold of 30- and 60-second commercials, longer doesn’t always mean better. “Whether it’s an ad, or a seven-minute piece, or a 17-episode series on Netflix,” said Hughes, “you have to approach it all with the same initial point of view: What is going to keep an audience engaged?” During the edit, brands and their collaborators should make cuts when and if it benefits the story they’re trying to tell, regardless of where it’ll be told.

Searching for a counter example, Ganguly pointed to her time at Conde Nast, where she produced the popular 73 Questions video series. The series is framed as a single shot walkthrough of a celebrity’s home, with the talent answering seventy-three rapid-fire questions. When Ganguly presented the first episode with Sarah Jessica Parker, her bosses felt that it was too long at six minutes. She tried explaining that there would be sound design and music that would change how the video would flow, but they could only see the length. “I think they were expecting it to be this massive failure, and I was getting ready to get fired,” she said.

Ganguly revealed that, before the video went live, she reached out to a contact at Buzzfeed and asked them to post it at the same time that Vogue did so that it would be seen by a much larger audience. Ultimately, the video’s length wasn’t an issue, and 73 Questions became one of the biggest digital series online. “It needs to be as long as it needs to be, and that’s it,” Ganguly said. “I don’t think editing this is going to make it interesting.”

With great length comes great responsibility

As branded videos and experiential activations become longer and more involved, brands and creators must remember that they’re asking viewers to commit to more. Guthrie believes experiences and films should be thoughtfully designed to respect the viewer’s time. Skipping unnecessary pre-roll and getting to the heart of the content will mean more engagement and greater receptivity to strapping in for the entire ride.

But how should longer stories be framed to keep audiences interested? Spoilers are the answer, according to McDonald. “As storytellers, naturally we want to hoard the end of our stories. We want to keep them secret, and we don’t want to give away the big reveal,” he said. “I found that it’s much more effective to give away what’s going to happen.”

With the deluge of content currently competing for the limited attention of audiences, it matters how quickly you get to the punchline. “You have to sort of give away your best parts, give away your ending to really entice and to get people to commit and invest that time,” McDonald added.

Everyone has to get their start in this industry somewhere. Maybe it’s as a runner, shuttling hard drives and other materials around town. Maybe it’s on the front desk, or directly as an assistant editor, colorist, or a logger. Then, eventually you not only move up steps in the industry, but you yourself get the chance to hire that next wave of post workers who will keep creating the content of the future.

Odds are when you start hiring, you’re going to assume that the people you are hiring will be a lot like you were at their age. However, that’s just no longer true. While every generation in human history has gripes about how “kids these days” are different than they were at the same age, there are some very real differences about the current generation of entry level workforce that need to be reckoned with if you are going to hire and onboard people properly.

While the exact boundaries of what defines each generation is an argument best left to the sociologist or the makers of memes, we’re going to go with “Generation Z” here to talk about this new wave of employees. If you are hiring an assistant who has recently entered the workforce, odds are the generation Z/zoomer label is the closest to one they’ll identify with.

References

The first thing to understand is that it’s no longer fair to assume the same base level of references for film and TV that applies to your generation. This point is one that frequently comes up in a complaint about this generation. “I asked them about Raiders of the Lost Ark and they hadn’t even seen it!” someone will say after an interview when discussing why they didn’t hire someone. “Clearly they aren’t serious about movies if they haven’t even seen Raiders.” While that specific example is due to age (Raiders came out 15 years before most zoomers were born), the bigger issue is the end of monoculture.

Even if you grew up with cable TV, if you are 30 or older odds are there were only a few cable channels that showed anything good. You had to go to the video store to get movies, where selection was limited. A lot of your choices about what you could even watch was incredibly limited by choices others had made for you. Yes, “The Shawshank Redemption” is a good movie, but it was also shown on cable movie channels nearly 24/7 for a period of years, so everyone you knew had seen it at least once without really trying. You could reasonably assume anyone “interested in movies” had seen it.

Zoomers have grown up with infinite media choice. Netflix (on disc, then streaming) was common, and they have always had everything available to them to watch and have gone down rabbit holes of niche exploration that just weren’t possible in years past. If you got into the french new wave in high school, you had maybe 5 movies you could watch at your video store or library, then you needed to mail order tapes or do inter library loan. The zoomers had all of everything ever created at their fingertips.

How do you deal with this? First off, understanding. Don’t judge your job applicants just because they haven’t seen some movie you love that comes up in the interview. It’s not a deliberate insult or a lack of curiosity that has left them without seeing the specific movies you think are important. It’s just how big the canon has become and the extreme increase in quantity of choice.

This also affects their education. If Zoomers did go to a media studies program, they still likely only had 1-2 “history” classes, with the rest often focused on other areas like production. That would mean only 30-60 films get assigned in those classes at most. It’s likely somewhere along the way someone asked them to watch “Citizen Kane,” but it’s also likely that there are a lot of films and media you consider vital that just never got assigned. You still hear people say things like: “You haven’t seen The Conformist? But I thought you went to film school!” which usually shows a lack of understanding for how little time some film programs put on film history and exactly how much film history there is out there to cover.

Secondly, if it’s important, create a references list for a project. Working on a horror film, it’s acceptable to suggest 5-6 films that should be watched to have the language of that project. The same applies in all media. Working on a historical doc TV show? Have a list of shows with which would like entry level employees to familiarize themselves.

Even in as mainstream a format as reality TV, there is so much content out there that you can’t assume familiarity with your individual show and its needs. Most new employees are eager to learn what they need to know to do their job well, and if that involves watching a few episodes of a given show that is very influential on your style, so be it.

Research

One common task of the new employee in post is research. Whether it’s knowing the newest workflows because they are fresh out of a training program, tracking down information on how to deal with a new file format or camera media coming in from production or even just chasing down answers to an Avid bug when the engineer is busy, junior employees are often given side research projects in between more routine more.

This generation has more successfully made the transition to video for information than previous generations. This means both that they would rather be trained with a video, and also that they are more likely to find video results for answers than film workers of even a decade ago. There is not only a huge film and post community on YouTube (such as Film Riot), but even TikTok is starting to be a place where people share small tips and tricks and solutions to workflow problems.

If you ask a new employee a question and instead of getting back to you with a forum link or a .pdf they respond with a TikTok link, that doesn’t mean they didn’t take the research problem seriously. It just might be where the best answer is to be found these days.

If you are creating new training materials, consider including more video content than you would have with previous efforts. With new audio search tools, it can be just as keyword searchable as a .pdf. And will often be more engaging.

Politics

One thing you might have heard frequently about the zoomer generation is that they expect a higher level of political engagement and “purity” from the companies they work for compared to previous generations. Some of this is purely fear mongering nonsense, but some of it is true, and it’s important to understand some context for the situation as you go about the hiring process.

The fear mongering nonsense is when you read headlines that young people are refusing to work or are expecting political alignment and purity from the companies they work for. That’s not the real experience for most of us hiring in post production. Young people are eager for jobs and paths into an industry they are passionate about. They want to work on projects that excite them, but they also are just excited to do the job and tend to have a pretty broad set of projects they are eager to work on. Recently, we did have one potential hire who heard we also worked in commercials and passed on a job because commercials as an entire concept “didn’t fit with their values,” but that candidate was actually over 30.

If you are working on projects for political campaigns, you’ll find that folks won’t want to work on projects they don’t support. And certain special topics such as working on an ad campaign for a bombing system will be difficult to staff. But largely, this generation understands that they won’t get to work on the perfect project all the time.

Zoomers are also more aware than previous generations of how valuable their skills are and how those skills contribute to a company. Whereas previous generations tended to focus more on getting any foot in the door and looked for raises as they moved from job to job, this generation is much more willing to actively negotiate for a raise quite early in the process (even just a few months after getting hired). This can be surprising the first time you experience it, since most of you who are now at the mid level had a year or more of low paying work as a way to “break in” to the industry. This generation is often less willing (or with rising housing prices less able) to do that.

Gen Z is also more interested in seeing a fair and equitable workplace and calling out management for situations they see as inappropriate. Asking someone to stay late without overtime to wait for a drive to get dropped off or a render to finish will get much more pushback from a zoomer than it used to.

It’s important to remember that just because we all had to do it doesn’t actually make it right. Oftentimes they are pushing back not just because they feel they should be paid overtime, but also because that’s the labor law. The film industry has always been notoriously lax about labor law enforcement since everyone is so eager to “prove themselves” and “move up the ladder” that they do whatever it takes to get ahead. This generation is more willing to put a focus on being treated fairly right now in a way that can feel aggressive the first few times you experience it.

Conclusion

As discussed at the top, every single generation in human history has had “kids these days” observations. The concept of a new generation having different values is nothing new. The key to remember is that it’s not the individual zoomer you are interacting with who changed; it’s the world they were raised in that changed around them.

They are likely just as eager and excited to be in this industry as you were at their age, but they are going to show it in different ways and with different boundaries. They are the future of the industry, and with a little consideration it can be invigorating to bring the next generation into the workplace. Show them what you’ve learned, and also learn from them.

For other tips on post-production, check out MediaSilo’s guide to Post Production Workflows.

MediaSilo allows for easy management of your media files, seamless collaboration for critical feedback and out of the box synchronization with your timeline for efficient changes. See how MediaSilo is powering modern post production workflows with a 14-day free trial.

For a TV series production, a show bible can be almost as important as the scripts themselves. Bibles are the definitive guide to a show, usually written by the series creator.

They cover every aspect of the series: characters, detailed story arcs, tone, theme, world, with episode breakdowns and ideas for future seasons. They’re mood boards. Bibles are a north star for a writing staff. However, bibles can also offer incredible pointers for post-production as well. Bibles can tell a team how to score a show, what the ideal pacing should be, whether to tease out the horror or the comedy in particular scenes, and so much more. Below are a few ways that editors and post-production supervisors can use series bibles to help inform their decisions.

Stranger Things

Perhaps one of the most iconic bibles ever produced, The Stranger Things bible, expertly establishes the show’s tone. The bible describes the ways in which the series will draw inspiration from 80s blockbusters. The visual style of the bible is also oozing with a classic Spielberg aesthetic. The writers also specifically call out John Carpenter. Editors reading the bible will be able to draw inspiration from those same 80s movies when it’s time to cut and color the series.

The Stranger Things bible also takes away a lot of the guesswork for post teams. The writers describe the soundtrack, and how the series should be scored to feel like movies from the era. It also explores the show’s approach to CGI and effects, making this document a true working roadmap for editors.

Freaks and Geeks

Freaks and Geeks was unlike any other teen show, and it wears that fact proudly on the first page of its bible. This series bible says that instead of glamorizing high school years, it’ll faithfully, and hilariously, explore all the discomfort and disorientation of high school. It spells out themes of confusion, isolation, yearning, sexual desire, wanting to fit in, and so much more. As a result, the series editors relied heavily on close shots and reaction shots in awkward moments to highlight the themes outlined in the bible, showing us the ways that the characters are processing and trying to navigate the strange newness of the world around them.

Fargo

Fargo’s bible opens with the premise that Fargo is not just a place or a movie title: it’s a genre. It’s a world of true crime and dark comedy and grittiness. Fargo’s four seasons span decades and cross state lines, but their visual style is consistent and all flows from that first page. Fargo’s world is cold, funny and cynical not just in the writing, but in its pace and it’s aesthetics. The bible is a roadmap to that style, and allows production teams to be unified in that vision from the first slug in the first script to the score of the closing credits.

The Wire

The Wire’s bible is one of the longest and most thorough bibles ever written. It peels back every layer of the show. It also establishes the city of Baltimore as a major character in the series. As a result, post-production teams found ingenious ways of bringing to life this character that had no dialogue from detailed establishing shots to fast, slice-of-life sequences. The result was a visual tapestry that inspired a generation of television, and a portrait of a city that every viewer immediately recognizes.

True Detective

This bible firmly establishes the two primary imperatives at the heart of the show: suspense, and humanism. The work that editors and post supervisors did on bringing these two themes to life shows up in the final product—the interplay between the plot, and the haunting drone shots or shots that seem to follow the detectives as they step into a world of danger. The show is stitched together in a way that can make the hairs on your neck stand up at a moment’s notice. But this series also had a way of finding the lightness in the dark, of bringing us back from the edge with the beauty of the landscape and the intimacy of its characters.

Summary

Each of these bibles is a masterclass in creating a road map for the people bringing the vision of a series to life. These aren’t just tools for writers and directors. Color, score, pace, focus all happen in post-production, but they stem from the ideas spelled out in the series bible. From highlighting visual comparisons, to demonstrating themes, these bibles are definitive guides on how post-production can continue to highlight a show’s themes and messages long after it’s been written and shot.

With that in mind, what are a few things that each stakeholder in the post workflow could stand to gain by ingraining a series bible in their creative process?

- Editors: Bibles often make distinct references to films or to eras of filmmaking. Editors can then use these bibles as North Stars for both style and pace. In Stranger Things, for example, the creators call out horror movies of the 80s, which allows an editor to draw inspiration from the editing styles of the time in order to align their work with the vision of the show’s creator. Similarly, if a show is intended to be built around episodic themes, editors can take cues from the bible on how to arrange shots and sequences to further underscores those themes.

- VFX Supervisors: Style is one of the core principles of a bible. Will the show aim for realism, or heightened science fiction, or will there be extended stunt shots like John Wick? As a bible explores these ideas, a VFX supervisor can begin to map out their work. Take The Wire, for example. The gritty realism spelled out in the bible suggests that violence in this show will be the polar opposite of the high octane VFX style of something like The Matrix, which was increasingly popular while The Wire was in development.

- Colorists: Bibles rely heavily on stills from movies and shows as well as stock photos, and are frequently put together by a graphic designer in order to reflect the aesthetics of the series. When looking at a bible and making decisions on how to approach post-production, a colorist can take cues from these components in order to align their work with the creator’s vision.

- Sound Designers: Bibles dedicate a significant portion of their word counts to defining a show’s tone and what an audience should be feeling as they’re watching. A sound designer can use this deep dive into tone as a roadmap for sound and score. For example, is a series supposed to be an ominous slow burn, or will it have fast-paced jump cuts? Bibles even sometimes call out specific musical artists, tracks, or other shows and movies they hope to emulate which can give further direction to sound designers.

- Post Production Supervisors: Bibles are often some of the most expressive pieces of development material. They try to encompass the full viewing experience in a single document, from screenwriting to camera work. They’re a roadmap for how the show should look. A post production supervisor can use these documents in order to see if the various steps in post are falling into place with the creator’s original vision.

For other tips on post-production, check out MediaSilo’s guide to Post Production Workflows.

MediaSilo allows for easy management of your media files, seamless collaboration for critical feedback and out of the box synchronization with your timeline for efficient changes. See how MediaSilo is powering modern post production workflows with a 14-day free trial.

Our guests from Green the Bid have a long history in the advertising industry, and are using that expertise to encourage their colleagues to think green when it comes to creating new advertising content.

Jessie Nagel – Founder – Green the Bid

Julian Katz – Founder – Green the Bid

Michael Kaliski – Founder – Green the Bid

Grace Amodeo – Program Manager – Shift

Grace:

Before we jump into Green the Bid, can each of you introduce yourselves and tell us about the work you do outside of this initiative?

Jessie:

I’m Jessie Nagel and I have a communications agency that I co-founded called Hype. We do PR communication and social media marketing, primarily for creative content providers behind the scenes in entertainment and advertising.

Julian:

I’m Julian Katz, I spent 23 years as an agency producer. And most recently have been working on contract at Facebook, helping to oversee all of our external agency production work including all of our DNI, sustainability, and other social impact programs.

Michael:

I’m Michael Kaliski, founder of Good Planet Innovation. We’re a sustainable production consultancy, originally from the film and television industry. And Good Planet also greens films, TV shows, and commercials.

Grace:

Michael, can you give us a little bit of context around the “green” initiative in film, television, and advertising? Where is this movement coming from, and where are we now?

Michael:

When I was in the film and television world, it was early days for this concept. When I first started in the nineties, nobody wanted to hear this conversation. They actually looked at me like I was a little bit crazy to even bring it up. In the 2000’s I had a production company geared toward humanitarian and environmental issues, but realized that we were generally preaching to the choir. So I started Good Planet, originally to integrate sustainable and ethical behavior on screen. And right after we launched we started to also look at the production aspect, and making productions zero waste and net carbon neutral. When we first started 10 years ago, it was really client driven. So the brand would mandate it and the mandate would roll down through the agency and then to the production company. We would execute the plan, but it was just a one-off – it was the exception, not the rule. A couple of years ago we started a partnership program which partnered with production companies, agencies, and brands to green their entire slate of productions. That was a great step in the right direction, but we don’t have time to do it one company at a time. Green the Bid was a natural evolution where we are engaging the entire industry, all the stakeholders from brands to agencies, production companies, post houses, and vendors to communicate together and share resources to make this a global movement.

That was a great step in the right direction, but we don’t have time to do it one company at a time. Green the Bid was a natural evolution where we are engaging the entire industry.

Grace:

How would you describe Green the Bid to someone who hasn’t heard of it before?

Jessie:

When we started talking with people many years ago about this, we heard that people were having difficulty being able to enact as many of the things that they wanted to do. So we said, how can we bring everybody together so that they can take their part of the responsibility and sort of link arms. I really agree that as a community we can try to affect change by identifying who is really responsible for what, and then learn from each other. We started to really talk about this in earnest well over a year ago, and we were ready to launch in March, but then the pandemic hit. Obviously it changed things for everybody because we were on pause, but it also provided us with an opportunity to dig a little deeper and really refine the way we want to develop this. We recognized in that moment a time where people maybe felt isolated, and it was time for us to really try to forge a community. And so that’s what we set out to do with Green the Bid.

Grace:

Since the advertising agency is so multi-faceted, how does Green to Bid engage with all of the different stakeholders?

Julian:

Well, the most important thing is that we elevate this conversation, that it becomes a top-of-mind consideration for all of the stakeholders. Just by asking people to think about it and talk about it, that’s what we’re doing with this work. But specifically, each sector is responsible for a different piece of the equation. So obviously the brand is the one that’s paying for the entire production. This is advertising for their products. So if there’s any financial consideration to having a sustainable production, that falls on the brand, and we ask that the brands accept that responsibility. The agencies are the next tier below the brands, the agencies are the ones coming up with the ideas, hiring the production companies and the post houses, et cetera. So the agencies we ask to advocate for the brands to pay for whatever is necessary to have a sustainable production, and to take responsibility for elevating this conversation to the advertisers. The production companies we ask to include a line item for sustainability, if there are costs associated with it, and that they defend that if challenged. For post houses it’s mostly about data storage and their energy plan within their office. And then each individual vendor, whether a caterer or a grip and electrical truck, is going to have very different considerations, but we have guidelines that we ask them to adhere to as best they can.

Jessie:

On the website we have guidelines so that people can reference the recommendations that we have. And a key part of it is this conversation point, which is really to bring the community together. We have member meetings on a quarterly basis, and we also have conversations in between. You can’t know everything, and we’re all often working in siloed ways. By talking to each other, things come up. And then we’re able to either address those or find the right people to be tasked to research something.

Grace:

Do you also advocate for sustainable practices being shown on screen, and not just in the process of the production?

Michael:

That’s a really important piece of it. We’re spending a little more time on the physical production bit right now, because the creative is really subjective and it’s up to the agency to make that happen. But we are definitely encouraging, in a non-prescriptive way, that they should be looking at their projects through that lens. For example if you had a party scene, everybody in that party should not be holding plastic cups. Even what’s on the grill, let’s have some more plant-based stuff on that grill. You don’t have to be preachy about it, you don’t have to point it out. But we present on screen aspirational characters, so we ought to have those characters behaving in a responsible way.

We present on screen aspirational characters, so we ought to have those characters behaving in a responsible way.

Grace:

How have you been outreaching to the community and spreading the word about Green the Bid?

Jessie:

We all work in these different aspects of the industry. So although we know a lot of the same people and our paths individually crossed many times, we do collectively have a pretty good network. So we started there, with the people that we know that have maybe even had conversations with us in the past about sustainability. In fact, because of COVID and because people are home, in some ways we had more opportunity to talk to people in a way that it would have been more difficult if we had to make an appointment to see them in an office. Another key part of it is partnering with various organizations, like D&AD and others who have an interest in this area. Even partners like AdGreen and Albert in the UK who are doing similar sustainable things.

Michael: