Ultimate EFS Series - NEW

The next-gen storage platform that's packed with more power, more speed, and unmatched performance—all at an unbeatable price

Ultimate NVMe - NEW

Experience unmatched speed, capacity, and efficiency with the new EditShare Ultimate NVMe

Ultimate EFS Field - NEW

Robust, portable media storage built on NVMe architecture offers unmatched speed, reliability, and up to 64TB of storage

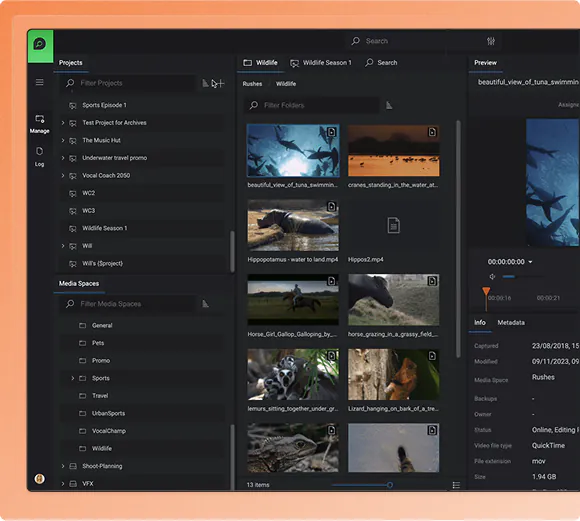

EFS 210 - NEW

Scalable, media-centric storage from 32TB to 432TB, paired with workflow tools to streamline production and foster collaboration

Ultimate 60NL - NEW

High-density parking node with in excess of 1.4PB of storage, unparalleled data protection, and cost-effective capacity to keep your production flowing

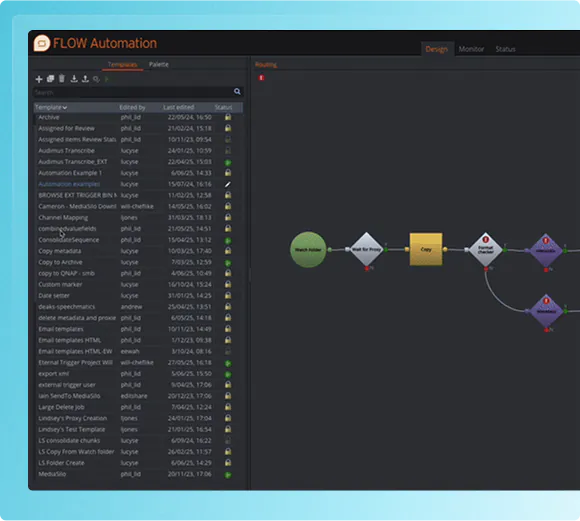

EFS 310 - NEW

High-performance, media-optimized storage in excess of 3PB with HA configurations, remote workflows, and advanced archiving to transform media production

Ultimate MDC - NEW

High-speed metadata controller ensures the smooth handling of large-scale data operations with unrivaled reliability and efficiency

EFS 410 - NEW

Enterprise-grade, scalable storage beyond 20PB with HA, unprecedented uptime, real-time analytics, and global workflow tools